The Book:

The Nutcracker and the Mouse King

The Nutcracker and the Mouse King

The Nutcracker and the Mouse King is a story written in 1816 by E. T. A. Hoffmann in which young Marie Stahlbaum’s favorite Christmas toy, the Nutcracker, comes alive and, after defeating the evil Mouse King in battle, whisks her away to a magical kingdom populated by dolls. In 1892, the Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and choreographers Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov turned the story into the ballet The Nutcracker, which became one of Tchaikovsky’s most famous compositions, and one of the most popular ballets in the world.

The story begins on Christmas Eve at the Stahlbaum house. Marie, twelve years old, and her brother Fritz, eight, sit outside the parlor speculating about what kind of present their godfather Drosselmeyer, who is a clockmaker and inventor, has made for them. They are at last allowed into the parlor, where they receive many splendid gifts, including Drosselmeyer’s, which turns out to be a clockwork castle with mechanical people moving about inside it. However, as the mechanical people can only do the same thing over and over without variation, the children quickly tire of it. At this point, Marie notices the Nutcracker doll, and asks whom he belongs to. Her father tells her that he belongs to all of them, but that since she is so fond of him she will be his special caretaker. Marie, her sister Louise, and her brother Fritz pass the Nutcracker among them, cracking nuts, until Fritz tries to crack a nut that is too big and hard, and the Nutcracker’s jaw breaks. Marie, upset, takes the Nutcracker away and bandages him with a ribbon from her dress.

When it is time for bed, the children put their Christmas gifts away in the special cupboard where they keep their toys. Fritz and Louise go up to bed, but Marie begs to be allowed to stay with Nutcracker a while longer, and she is allowed to do so. She puts Nutcracker to bed and tells him that Drosselmeyer will fix his jaw as good as new. At this, the Nutcracker’s face seems momentarily to come alive, and Marie is frightened, but she then decides it was only her imagination.

The grandfather clock begins to chime, and Marie believes she sees Drosselmeyer sitting on top of it, preventing it from striking. Mice begin to come out from beneath the floor boards, including the seven-headed Mouse King. Marie, startled, slips and puts her elbow through the glass door of the toy cupboard. The dolls in the cupboard come alive and begin to move, Nutcracker taking command and leading them into battle after putting Marie’s ribbon on as a token. The battle at first goes to the dolls, but they are eventually overwhelmed by the mice. Marie, seeing Nutcracker about to be taken prisoner, takes off her shoe and throws it at the Mouse King, then faints.

Marie wakes the next morning with her arm bandaged and tries to tell her parents about the battle between the mice and the dolls, but they do not believe her, thinking that she has had a fever dream caused by the wound she sustained from the broken glass. Drosselmeyer soon arrives with the Nutcracker, whose jaw has been fixed, and tells Marie the story of Princess Pirlipat and the Queen of the Mice, which explains how Nutcrackers came to be and why they look the way they do.

The Queen of the Mice tricked Pirlipat’s mother into allowing her and her children to gobble up the lard that was supposed to go into the sausage that the King was to eat at dinner that evening. The King, enraged at the Mouse Queen for spoiling his supper and upsetting his wife, had his court inventor, whose name happens to be Drosselmeyer, create traps for the Mouse Queen and her children.

The Mouse Queen, angered at the death of her children, swore that she would take revenge on the King’s daughter, Pirlipat. Pirlipat’s mother surrounded her with cats which were supposed to be kept awake by being constantly stroked, however inevitably the nurses who stroked the cats fell asleep and the Mouse Queen magically turned the infant Pirlipat ugly, giving her a huge head, a wide grinning mouth and a cottony beard, like a nutcracker. The King blamed Drosselmeyer and gave him four weeks to find a cure. At the end of four weeks, Drosselmeyer had no cure but went to his friend, the court astrologer.

They read Pirlipat’s horoscope and told the King that the only way to cure her was to have her eat the nut Crackatook, which must be cracked and handed to her by a man who had never been shaved nor worn boots since birth, and who must, without opening his eyes hand her the kernel and take seven steps backwards without stumbling. The King sent Drosselmeyer and the astrologer out to look for the nut and the young man, charging them on pain of death not to return until they had found them.

The two men journeyed for many years without finding either the nut or the man, until finally they returned home and found the nut in a small shop. The man who had never been shaved and never worn boots turned out to be Drosselmeyer’s own nephew. The King, once the nut had been found, promised his daughter’s hand to whoever could crack the nut. Many men broke their teeth on the nut before Drosselmeyer’s nephew finally appeared. He cracked the nut easily and handed it to the princess, who swallowed it and immediately became beautiful again, but Drosselmeyer’s nephew, on his seventh backward step, trod on the Queen of the Mice and stumbled, and the curse fell on him, giving him a large head, wide grinning mouth and cottony beard; in short, making him a Nutcracker. The ungrateful Princess, seeing how ugly Drosselmeyer’s nephew had become, refused to marry him and banished him from the castle.

Marie, while she recuperates from her wound, hears the King of the Mice whispering to her in the middle of the night, threatening to bite Nutcracker to pieces unless she gives him her sweets and her dolls. For Nutcracker’s sake, Marie sacrifices her things, but the Mouse king wants more and more and finally Nutcracker tells Marie that if she will just get him a sword, he will finish the Mouse King. Marie asks Fritz for a sword for Nutcracker, and he gives her the sword of one of his toy hussars. The next night, Nutcracker comes into Marie’s room bearing the Mouse King’s seven crowns, and takes her away with him to the doll kingdom, where Marie sees many wonderful things. She eventually falls asleep in the Nutcracker’s palace and is brought back home. She tries to tell her mother what happened, but again she is not believed, even when she shows her parents the seven crowns, and she is forbidden to speak of her “dreams” anymore.

As Marie sits in front of the toy cabinet one day, looking at Nutcracker and thinking about all the wondrous things that happened, she can’t keep silent anymore and swears to the Nutcracker that if he were ever really real she would never behave as Princess Pirlipat behaved, and she would love him whatever he looked like. At this, there is a bang and she falls off the chair. Her mother comes in to tell her that godfather Drosselmeyer has arrived with his young nephew. Drosselmeyer’s nephew takes Marie aside and tells her that by swearing that she would love him in spite of his looks, she broke the curse on him and made him handsome again. He asks her to marry him. She accepts, and in a year and a day he comes for her and takes her away to the Doll Kingdom, where she is crowned queen.

01-05- Tchaikovsky The Nutcracker Suite, Op 71A – 10 Waltz Of The Flow

The Ballet: The Nutcracker

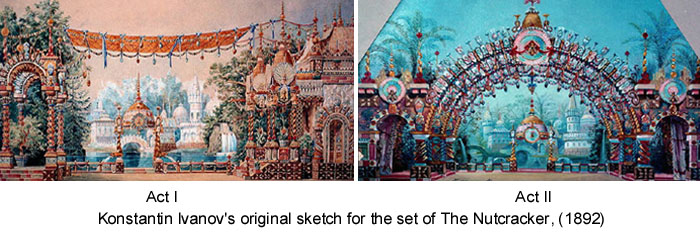

The Nutcracker, Op. 71, is a fairy tale-ballet in two acts, three scenes, by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, composed in 1891–92. Alexandre Dumas père’s adaptation of the story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann was set to music by Tchaikovsky. (staged by Marius Petipa and commissioned by the directoQr of the Imperial Theatres Ivan Vsevolozhsky in 1891). The plot of Hoffmann’s story is much more elaborate than that of the ballet; in the tale, the heroine Marie’s adventures with the toys and with the Nutcracker are not a dream, and at the end she marries the Nutcracker/Prince.

In 1892 at an assembly of the St. Petersburg branch of the Musical Society. er is noted for its use of the celesta, an instrument that is well-known in The Nutcracker as the featured solo instrument in the “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” f

Tchaikovsky himself was less satisfied with The Nutcracker than with The Sleeping Beauty, his previous ballet. (In the film Fantasia, commentator Deems Taylor observes, very accurately, that he “really detested” the score.) Though he accepted the commission from Ivan Vsevolozhsky, he did not particularly want to write it (though he did write to a friend while composing the ballet: “I am daily becoming more and more attuned to my task.”)

While composing the music for the ballet, Tchaikovsky is said to have argued with a friend who wagered that the composer could not write a melody based on the notes of the octave in sequence. Tchaikovsky asked if it mattered whether the notes were in ascending or descending order, and was assured it did not. This resulted in the Grand adagio from the Grand pas de deux of the second act, which traditionally is danced just after the Waltz of the Flowers.

A story is also told that Tchaikovsky’s sister had died shortly before he began composition of the ballet, and that his sister’s death influenced him to compose a melancholy, descending scale melody for the adagio of the Grand Pas de Deux.

Premiere

The first performance of the ballet was held as a double premiere together with Tchaikovsky’s last opera Iolanta on 18 December 1892, at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia. In other countries, An abridged version of the ballet was first performed outside Russia in Budapest (Royal Opera House) in 1927. The first complete performance of the ballet outside Russia took place in England in 1934. The ballet’s first complete United States performance was in 1944. The tradition of performing the complete “Nutcracker” at Christmas eventually spread to the rest of the United States.

The Nutcracker: a ballet in two acts.

The plot revolves around a German girl named Clara Stahlbaum or Clara Silberhaus. In some Nutcracker productions, Clara is called Marie; in others, she is known as Masha. (In Hoffmann’s tale, the girl’s name actually is Marie or Maria, while Clara is the name of one of her dolls.

Characters

- President

- His wife

- Their children:

- Clara [Marie]

- Fritz

- Marianna, the President’s niece

- Councilor Drosselmeyer, Godfather of Clara and Fritz

- Nutcracker

- Sugar Plum Fairy, sovereign of sweets

- Prince Koklyush [Orgeat]

- Major-domo

- Harlequin

- Aunt Milli

- Soldier

- Columbine

- Mama Gigogne [Mother Ginger]

- Mouse King

- Relatives, guests, people in costume, children, servants, mice, dolls, hares, toys, soldiers, gnomes, snowflakes, fairies, sweets, pastries, sweetmeats, moors, pages, princesses, retinues, buffoons, shepherdesses, flowers, etc.

Act I

The work opens with a brief “Miniature Overture”, which also opens the Suite. The music sets the fairy mood by using upper registers of the orchestra exclusively. The curtain opens to reveal the Stahlbaums’ house, where a Christmas Eve party is under way. Clara, her little brother Fritz, and their mother and father are celebrating with friends and family, when the mysterious godfather, Herr Drosselmeyer, enters. He quickly produces a large bag of gifts for all the children. All are very happy, except for Clara, who has yet to be presented a gift. Herr Drosselmeyer then produces three life-size dolls, which each take a turn to dance. When the dances are done, Clara approaches Herr Drosselmeyer asking for her gift. It would seem that he is out of presents, and Clara, in some productions, runs to her mother in a fit of tears and disappointment. In others, she is still quite happy or she whispers into Drosselmeyer’s ear, presumably gently hinting that she would like a toy.

Drosselmeyer then produces a toy Nutcracker, in the traditional shape of a soldier in full parade uniform. Clara is overjoyed, but her brother Fritz is jealous, and breaks the Nutcracker.

The party ends with Tchaikovsky quoting the traditional German dance tune, the Grossvater Tanz, and the Stahlbaum family go to bed. In some version, while everybody is sleeping, Herr Drosselmeyer repairs the Nutcracker, but in most productions, he simply binds it with a handkerchief during the Christmas party. Clara creeps downstairs to have a look at her beloved Nutcracker. When the clock strikes midnight, Clara hears the sound of mice. She wakes up (or is she still dreaming?) and tries to run away, but the mice stop her. In most productions, the Christmas tree suddenly begins to grow to enormous size, filling the room. The Nutcracker comes to life, he and his band of soldiers rise to defend Clara, and the Mouse King leads his mice into battle. Here Tchaikovsky continues the miniature effect of the Overture, setting the battle music predominantly in the orchestra’s upper registers.

A conflict ensues, and when Clara helps the Nutcracker by throwing her shoe at the Mouse King, the Nutcracker seizes his opportunity and stabs him. The mouse dies. In some productions, she merely grabs the Mouse King by the tail, and in others Clara kills the Mouse King when she throws her slipper at him. The mice retreat, taking their dead leader with them. The Nutcracker is then transformed into a prince. In Hoffmann’s original story, the Prince is actually Drosselmeyer’s nephew, who had been turned into a Nutcracker by the Mouse King, and all the events following the Christmas party have been arranged by Drosselmeyer in order to break the spell.

Clara and the Prince travel to a world where dancing Snowflakes greet them and fairies and queens dance, welcoming Clara and the Prince into their world. The score conveys the wondrous images by introducing a wordless children’s chorus.

The curtain falls on Act I.

Act II

Clara and the Prince arrive at the Land of the Sugar Plum Fairy. The Sugar Plum Fairy and the people of the Land of Sweets perform several dances for Clara and the Prince – a Spanish Dance (sometimes Chocolate), ta Chinese Dance (sometimes Tea), an Arabian Dance (sometimes Coffee), a Russian dance (in Balanchine’s production, performed by Candy Canes — their dance is called the Trepak), the Dance of the Clowns, performed by Mother Ginger and her Polichinelles – sometimes Bonbons, Taffy Clowns, or Court Buffoons (as in Baryshnikov’s production), the Dance of the Reed Flutes (sometimes Marzipan shepherds or mirlitons), the Waltz of the Flowers, and the Grand Pas de Deux, which includes the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. The dances in the Land of the Sugar Plum Fairy are not always performed in this order

After the festivities, Clara wakes up under the Christmas tree with the Nutcracker toy in her arms and the curtain closes. (In Balanchine’s version, however, she is never shown waking up; instead, after all the dances in the Kingdom of Sweets have concluded, she rides off with the Nutcracker/Prince on a Santa Claus-like flying sleigh, complete with reindeer, and the curtain falls. This gives the impression that the “dream” actually happens in reality, as in Hoffmann’s original story. since at the end, Drosselmeyer’s nephew, who had really been transformed into a nutcracker, reappears in human form at the toymaker’s shop.

The Music

Song Title

- The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Overture

- The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 1

– The Christmas Tree - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 2

– March - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 3

– Galop and Dance of the Parents - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 4

– Dance Scene – The Presents of Drosselmeyer - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 5

– Scene – Grandfather Dance - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 6

– Clara and the Nutcracker - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 7

– The Nutcracker Battles the Army of the Mouse King – He Wins and Is Transformed into Prince Charming - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 8

– In the Christmas Tree - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 1 – No. 9

– Scene and Waltz of the Snowflakes - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 10

– The Magic Castle on the Mountain of Sweets - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 11

– Clara and Prince Charming - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 12a

– Character Dances: Chocolate (Spanish Dance) - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 12b

– Character Dances: Coffee (Arabian Dance) - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 12c

– Character Dances: Tea (Chinese Dance) - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 12d

Character Dances: Trépak (Russian Dance) - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 12e

– Character Dances: Dance of the Reed Pipes - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 12f

– Character Dances: Polchinelle (The Clown) - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 13

– Waltz of the Flowers - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 14a

– Pas de deux: Intrada - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 14b

– Pas de deux: Variation I (Tarantella) - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 14c

– Pas de deux: Variation II (Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy) - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 14d

– Pas de deux: Coda - The Nutcracker, Op.71 – Act 2 – No. 15

– Final Waltz and Apotheosis

The music in Tchaikovsky’s ballet is some of the composer’s most popular. The music belongs to the Romantic Period and contains some of his most memorable melodies, several of which are frequently used in television and film. They are often heard in TV commercials shown during the Christmas season. The Trepak, or Russian dance, is one of the most recognizable pieces in the ballet, along with the famous Waltz of the Flowers and March, as well as the ubiquitous Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. The ballet contains surprisingly advanced harmonies and a wealth of melodic invention that is (to many) unsurpassed in ballet music. Nevertheless, the composer’s reverence for Rococo and late 18th century music can be detected in passages such as the Overture, the “Entrée des parents”, and “Tempo di Grossvater” in Act I.

One novelty in Tchaikovsky’s original score was the use of the celesta [1], a new instrument Tchaikovsky had discovered in Paris. He wanted it genuinely for the character of the Sugar Plum Fairy to characterize her because of its “heavenly sweet sound”. It appears not only in her “Dance”, but also in other passages in Act II. Tchaikovsky also uses toy instruments during the Christmas party scene. Tchaikovsky was proud of the celesta’s effect, and wanted its music performed quickly for the public, before he could be “scooped.” Everyone was enchanted.

Suites derived from this ballet became very popular on the concert stage. The composer himself extracted a suite of eight pieces from the ballet, but that authoritative move has not prevented later hands from arranging other selections and sequences of numbers. Eventually one of these ended up in Disney’s Fantasia. In any case, The Nutcracker Suite should not be mistaken for the complete ballet.

Although the original ballet is only about 85 minutes long, and therefore much shorter than either Swan Lake or The Sleeping Beauty, some modern staged performances have omitted or re-ordered some of the music, or inserted selections from elsewhere, thus adding to the confusion over the suites. In fact, most of the very famous versions of the ballet have had the order of the dances slightly re-arranged, if they have not actually altered the music.

[1] Celesta, A musical instrument with a keyboard and metal plates struck by hammers that produce bell-like tones. A keyboard instrument in the form of a small upright piano invented by Auguste Mustel in 1866; metal plates suspended over resonating boxes are struck by hammers and sustained after the manner of the piano action. Its compass is five octaves from c; it is written an octave below sounding pitch.