Abraham Lincoln, 16th president of the United States, guided the nation through its devastating Civil War and remains much beloved and honored as one of the world’s great leaders.

Lincoln was born in Hardin (now Larue) County, Kentucky grew up in abject poverty. He moved with his family to frontier Indiana in 1816, and then to Illinois in 1830. Although Lincoln had only about eighteen months of formal education, he was an avid reader and made extraordinary efforts to gain knowledge while working at many jobs, from farm hand to store clerk. Lincoln served briefly in the Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War of 1832. Also that year, he also began his political career with a failed campaign for a seat in the Illinois General Assembly but was elected to the Assembly in 1834. In November 1842, he married Mary Todd (1818–1882), daughter of a prominent Kentucky slave-owning family. The couple settled in Springfield, Illinois, where their four sons—Robert, Edward, William, and Thomas (Tad)—were born.

After serving four terms in the Illinois legislature during which time he also established a successful law practice, Lincoln was elected as a Whig party to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846. He did not seek reelection and returned to Springfield, Illinois. Although unsuccessful as a Whig candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1855, Lincoln was the newly formed Republican Party’s standard-bearer for the same seat three years later. In that race, Lincoln captured national recognition by engaging Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in a dramatic series of public debates, but Lincoln ultimately lost to Douglas on election day.

In 1860 Lincoln was elected the nation’s first Republican president. By the time of his inauguration in March 1861, seven Southern states had seceded from the Union, formed their own separate government, and inaugurated Jefferson Davis as its president. Concerned with preserving the Union from dissolution, Lincoln presented an inaugural address that was conciliatory in nature, assuring that slavery would not be abolished where it then existed. But one month later, when Confederate forces opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston South Carolina while Congress was in recess, Lincoln acted decisively. He called up the militia; proclaimed a blockade; and suspended the writ of habeas corpus, which ensures a citizen’s right to be brought before a court before imprisonment. The war that ensued lasted for four years (1861-1865), during which time Lincoln assumed greater executive power than any previous U.S. president.

Of all Lincoln’s actions during the American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 9, 1865), he is perhaps best remembered for the Emancipation Proclamation, which he issued on January 1, 1863. Although it did not abolish slavery nationwide, it put slaveholders on notice and gave the conflict an undeniable moral imperative.

In 1864, Lincoln was reelected to the presidency, carrying fifty-four percent of the popular vote and all but three northern states—New Jersey, Delaware, and Kentucky. Lincoln was assassinated on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on that same day that the Federal flag was formally raised at Fort Sumter, where almost four years to the day the Civil War began. His plan for postwar reconstruction advocated the forming of new state governments that would be loyal to the Union, a plan later adopted by President Andrew Johnson.

Inaugural Address: March 04, 1861

Fellow-Citizens of the United States:

In compliance with a custom as old as the Government itself, I appear before you to address you briefly and to take in your presence the oath prescribed by the Constitution of the United States to be taken by the President “before he enters on the execution of this office.”

I do not consider it necessary at present for me to discuss those matters of administration about which there is no special anxiety or excitement.

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that–

I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.

Those who nominated and elected me did so with full knowledge that I had made this and many similar declarations and had never recanted them; and more than this, they placed in the platform for my acceptance, and as a law to themselves and to me, the clear and emphatic resolution which I now read:

‘Resolved’, That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes.

I now reiterate these sentiments, and in doing so I only press upon the public attention the most conclusive evidence of which the case is susceptible that the property, peace, and security of no section are to be in any wise endangered by the now incoming Administration. I add, too, that all the protection which, consistently with the Constitution and the laws, can be given will be cheerfully given to all the States when lawfully demanded, for whatever cause–as cheerfully to one section as to another.

There is much controversy about the delivering up of fugitives from service or labor. The clause I now read is as plainly written in the Constitution as any other of its provisions:

No person held to service or labor in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall in consequence of any law or regulation therein be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.

It is scarcely questioned that this provision was intended by those who made it for the reclaiming of what we call fugitive slaves; and the intention of the lawgiver is the law. All members of Congress swear their support to the whole Constitution–to this provision as much as to any other. To the proposition, then, that slaves whose cases come within the terms of this clause “shall be delivered up” their oaths are unanimous. Now, if they would make the effort in good temper, could they not with nearly equal unanimity frame and pass a law by means of which to keep good that unanimous oath?

There is some difference of opinion whether this clause should be enforced by national or by State authority, but surely that difference is not a very material one. If the slave is to be surrendered, it can be of but little consequence to him or to others by which authority it is done. And should anyone in any case be content that his oath shall go unkept on a merely unsubstantial controversy as to ‘how’ it shall be kept?

Again: In any law upon this subject ought not all the safeguards of liberty known in civilized and humane jurisprudence to be introduced, so that a free man be not in any case surrendered as a slave? And might it not be well at the same time to provide by law for the enforcement of that clause in the Constitution which guarantees that “the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States”?

I take the official oath to-day with no mental reservations and with no purpose to construe the Constitution or laws by any hypercritical rules; and while I do not choose now to specify particular acts of Congress as proper to be enforced, I do suggest that it will be much safer for all, both in official and private stations, to conform to and abide by all those acts which stand unrepealed than to violate any of them trusting to find impunity in having them held to be unconstitutional.

It is seventy-two years since the first inauguration of a President under our National Constitution. During that period fifteen different and greatly distinguished citizens have in succession administered the executive branch of the Government. They have conducted it through many perils, and generally with great success. Yet, with all this scope of precedent, I now enter upon the same task for the brief constitutional term of four years under great and peculiar difficulty. A disruption of the Federal Union, heretofore only menaced, is now formidably attempted.

I hold that in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments. It is safe to assert that no government proper ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination. Continue to execute all the express provisions of our National Constitution, and the Union will endure forever, it being impossible to destroy it except by some action not provided for in the instrument itself.

Again: If the United States be not a government proper, but an association of States in the nature of contract merely, can it, as a contract, be peaceably unmade by less than all the parties who made it? One party to a contract may violate it–break it, so to speak–but does it not require all to lawfully rescind it?

Descending from these general principles, we find the proposition that in legal contemplation the Union is perpetual confirmed by the history of the Union itself. The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured, and the faith of all the then thirteen States expressly plighted and engaged that it should be perpetual, by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was “to form a more perfect Union.”

But if destruction of the Union by one or by a part only of the States be lawfully possible, the Union is ‘less’ perfect than before the Constitution, having lost the vital element of perpetuity.

It follows from these views that no State upon its own mere motion can lawfully get out of the Union; that ‘resolves’ and ‘ordinances’ to that effect are legally void, and that acts of violence within any State or States against the authority of the United States are insurrectionary or revolutionary, according to circumstances.

I therefore consider that in view of the Constitution and the laws the Union is unbroken, and to the extent of my ability, I shall take care, as the Constitution itself expressly enjoins upon me, that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the States. Doing this I deem to be only a simple duty on my part, and I shall perform it so far as practicable unless my rightful masters, the American people, shall withhold the requisite means or in some authoritative manner direct the contrary. I trust this will not be regarded as a menace, but only as the declared purpose of the Union that it ‘will’ constitutionally defend and maintain itself.

In doing this there needs to be no bloodshed or violence, and there shall be none unless it be forced upon the national authority. The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere. Where hostility to the United States in any interior locality shall be so great and universal as to prevent competent resident citizens from holding the Federal offices, there will be no attempt to force obnoxious strangers among the people for that object. While the strict legal right may exist in the Government to enforce the exercise of these offices, the attempt to do so would be so irritating and so nearly impracticable withal that I deem it better to forego for the time the uses of such offices.

The mails, unless repelled, will continue to be furnished in all parts of the Union. So far as possible the people everywhere shall have that sense of perfect security which is most favorable to calm thought and reflection. The course here indicated will be followed unless current events and experience shall show a modification or change to be proper, and in every case and exigency my best discretion will be exercised, according to circumstances actually existing and with a view and a hope of a peaceful solution of the national troubles and the restoration of fraternal sympathies and affections.

That there are persons in one section or another who seek to destroy the Union at all events and are glad of any pretext to do it I will neither affirm nor deny; but if there be such, I need address no word to them. To those, however, who really love the Union may I not speak?

Before entering upon so grave a matter as the destruction of our national fabric, with all its benefits, its memories, and its hopes, would it not be wise to ascertain precisely why we do it? Will you hazard so desperate a step while there is any possibility that any portion of the ills you fly from have no real existence? Will you, while the certain ills you fly to are greater than all the real ones you fly from, will you risk the commission of so fearful a mistake?

All profess to be content in the Union if all constitutional rights can be maintained. Is it true, then, that any right plainly written in the Constitution has been denied? I think not. Happily, the human mind is so constituted that no party can reach to the audacity of doing this. Think, if you can, of a single instance in which a plainly written provision of the Constitution has ever been denied. If by the mere force of numbers a majority should deprive a minority of any clearly written constitutional right, it might in a moral point of view justify revolution; certainly would if such right were a vital one. But such is not our case. All the vital rights of minorities and of individuals are so plainly assured to them by affirmations and negations, guaranties and prohibitions, in the Constitution that controversies never arise concerning them. But no organic law can ever be framed with a provision specifically applicable to every question which may occur in practical administration. No foresight can anticipate nor any document of reasonable length contain express provisions for all possible questions. Shall fugitives from labor be surrendered by national or by State authority? The Constitution does not expressly say. ‘May’ Congress prohibit slavery in the Territories? The Constitution does not expressly say. ‘Must’ Congress protect slavery in the Territories? The Constitution does not expressly say.

From questions of this class spring all our constitutional controversies, and we divide upon them into majorities and minorities. If the minority will not acquiesce, the majority must, or the Government must cease. There is no other alternative, for continuing the Government is acquiescence on one side or the other. If a minority in such case will secede rather than acquiesce, they make a precedent which in turn will divide and ruin them, for a minority of their own will secede from them whenever a majority refuses to be controlled by such minority. For instance, why may not any portion of a new confederacy a year or two hence arbitrarily secede again, precisely as portions of the present Union now claim to secede from it? All who cherish disunion sentiments are now being educated to the exact temper of doing this.

Is there such perfect identity of interests among the States to compose a new union as to produce harmony only and prevent renewed secession?

Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it does of necessity fly to anarchy or to despotism. Unanimity is impossible. The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy or despotism in some form is all that is left.

I do not forget the position assumed by some that constitutional questions are to be decided by the Supreme Court, nor do I deny that such decisions must be binding in any case upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit, while they are also entitled to very high respect and consideration in all parallel cases by all other departments of the Government. And while it is obviously possible that such decision may be erroneous in any given case, still the evil effect following it, being limited to that particular case, with the chance that it may be overruled and never become a precedent for other cases, can better be borne than could the evils of a different practice. At the same time, the candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal. Nor is there in this view any assault upon the court or the judges. It is a duty from which they may not shrink to decide cases properly brought before them, and it is no fault of theirs if others seek to turn their decisions to political purposes.

One section of our country believes slavery is ‘right’ and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is ‘wrong’ and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute. The fugitive-slave clause of the Constitution and the law for the suppression of the foreign slave trade are each as well enforced, perhaps, as any law can ever be in a community where the moral sense of the people imperfectly supports the law itself. The great body of the people abide by the dry legal obligation in both cases, and a few break over in each. This, I think, can not be perfectly cured, and it would be worse in both cases ‘after’ the separation of the sections than before. The foreign slave trade, now imperfectly suppressed, would be ultimately revived without restriction in one section, while fugitive slaves, now only partially surrendered, would not be surrendered at all by the other.

Physically speaking, we can not separate. We can not remove our respective sections from each other nor build an impassable wall between them. A husband and wife may be divorced and go out of the presence and beyond the reach of each other, but the different parts of our country can not do this. They can not but remain face to face, and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them. Is it possible, then, to make that intercourse more advantageous or more satisfactory ‘after’ separation than ‘before’? Can aliens make treaties easier than friends can make laws? Can treaties be more faithfully enforced between aliens than laws can among friends? Suppose you go to war, you can not fight always; and when, after much loss on both sides and no gain on either, you cease fighting, the identical old questions, as to terms of intercourse, are again upon you.

This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing Government, they can exercise their ‘constitutional’ right of amending it or their ‘revolutionary’ right to dismember or overthrow it. I can not be ignorant of the fact that many worthy and patriotic citizens are desirous of having the National Constitution amended. While I make no recommendation of amendments, I fully recognize the rightful authority of the people over the whole subject, to be exercised in either of the modes prescribed in the instrument itself; and I should, under existing circumstances, favor rather than oppose a fair opportunity being afforded the people to act upon it. I will venture to add that to me the convention mode seems preferable, in that it allows amendments to originate with the people themselves, instead of only permitting them to take or reject propositions originated by others, not especially chosen for the purpose, and which might not be precisely such as they would wish to either accept or refuse. I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution–which amendment, however, I have not seen–has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service. To avoid misconstruction of what I have said, I depart from my purpose not to speak of particular amendments so far as to say that, holding such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable.

The Chief Magistrate derives all his authority from the people, and they have referred none upon him to fix terms for the separation of the States. The people themselves can do this if also they choose, but the Executive as such has nothing to do with it. His duty is to administer the present Government as it came to his hands and to transmit it unimpaired by him to his successor.

Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better or equal hope in the world? In our present differences, is either party without faith of being in the right? If the Almighty Ruler of Nations, with His eternal truth and justice, be on your side of the North, or on yours of the South, that truth and that justice will surely prevail by the judgment of this great tribunal of the American people.

By the frame of the Government under which we live this same people have wisely given their public servants but little power for mischief, and have with equal wisdom provided for the return of that little to their own hands at very short intervals. While the people retain their virtue and vigilance no Administration by any extreme of wickedness or folly can very seriously injure the Government in the short space of four years.

My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and ‘well’ upon this whole subject. Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time. If there be an object to ‘hurry’ any of you in hot haste to a step which you would never take ‘deliberately’, that object will be frustrated by taking time; but no good object can be frustrated by it. Such of you as are now dissatisfied still have the old Constitution unimpaired, and, on the sensitive point, the laws of your own framing under it; while the new Administration will have no immediate power, if it would, to change either. If it were admitted that you who are dissatisfied hold the right side in the dispute, there still is no single good reason for precipitate action. Intelligence, patriotism, Christianity, and a firm reliance on Him who has never yet forsaken this favored land are still competent to adjust in the best way all our present difficulty.

In ‘your’ hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in ‘mine’, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail ‘you’. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. ‘You’ have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect, and defend it.”

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Gettysburg Address: November 19, 1863

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Emancipation Proclamation: January 01, 1863

Proclamation 95—Regarding the Status of Slaves in States Engaged in Rebellion Against the United States

“That on the 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

“That the Executive will on the 1st day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State or the people thereof shall on that day be in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such States shall have participated shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State and the people thereof are not then in rebellion against the United States.”

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and Government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, and in accordance with my purpose so to do, publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof, respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkeley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Anne, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts are for the present left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States and parts of States are and henceforward shall be free, and that the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense; and I recommend to them that in all cases when allowed they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

By the President:

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

Inaugural Address: March 04, 1865

FELLOW-COUNTRYMEN:

At this second appearing to take the oath of the Presidential office there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement somewhat in detail of a course to be pursued seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself, and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war-seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

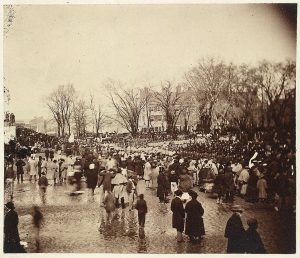

Crowd at Lincoln’s second inauguration, March 4, 1865

Crowd at Lincoln’s second inauguration, March 4, 1865

Photo shows a large crowd of people waiting during President Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, which was held on a rainy day at the U.S. Capitol grounds in Washington, D.C. The crowd includes African American troops who marched in the inaugural parade. In considering the Civil War that had begun in 1861 and was nearing conclusion, Lincoln ended his speech with the famous phrase: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, … let us strive on to finish the work we are in, … to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” In the background are Congressional boarding houses on A Street, N.E., between Delaware Ave. and First Street, N.E.

The President’s Last Public Address

By these recent successes the reinauguration of the national authority—reconstruction—which has had a large share of thought from the first, is pressed much more closely upon our attention. It is fraught with great difficulty. Unlike a case of war between independent nations, there is no authorized organ for us to treat with — no one man has authority to give up the rebellion for any other man. We simply must begin with and mold from disorganized and discordant elements. Nor is it a small additional embarrassment that we, the loyal people, differ among ourselves as to the mode, manner, and measure of reconstruction. As a general rule, I abstain from reading the reports of attacks upon myself, wishing not to be provoked by that to which I cannot properly offer an answer. In spite of this precaution, however, it comes to my knowledge that I am much censured for some supposed agency in setting up and seeking to sustain the new State government of Louisiana.

In this I have done just so much as, and no more than, the public knows. In the annual message of December, 1863, and in the accompanying proclamation, I presented a plan of reconstruction, as the phrase goes, which I promised, if adopted by any State, should be acceptable to and sustained by the executive government of the nation. I distinctly stated that this was not the only plan which might possibly be acceptable, and I also distinctly protested that the executive claimed no right to say when or whether members should be admitted to seats in Congress from such States. This plan was in advance submitted to the then Cabinet, and distinctly approved by every member of it One of them suggested that I should then and m that connection apply the Emancipation Proclamation to the theretofore excepted parts of Virginia and Louisiana; that I should drop the suggestion about apprenticeship for freed people, and that I should omit the protest against my own power in regard to the admission of members to Congress. But even he approved every part and parcel of the plan which has since been employed or touched by the action of Louisiana.

The new constitution of Louisiana, declaring emancipation for the whole State, practically applies the proclamation to the part previously excepted. It does not adopt apprenticeship for freed people, and it is silent, as it could not well be otherwise, about the admission of members to Congress. So that, as it applies to Louisiana, every member of the Cabinet fully approved the plan. The message went to Congress, and I received many commendations of the plan, written and verbal, and not a single objection to it from any professed emancipationist came to my knowledge until after the news reached Washington that the people of Louisiana had begun to move in accordance with it. From about July, 1862, I had corresponded with different persons supposed to be interested [in] seeking a reconstruction of a State government for Louisiana. When the message of 1863, with the plan before mentioned, reached New Orleans, General Banks wrote me that he was confident that the people, with his military cooperation, would reconstruct substantially on that plan. I wrote to him and some of them to try it. They tried it, and the result is known. Such has been my only agency in getting up the Louisiana government.

As to sustaining it, my promise is out, as before stated. But as bad promises are better broken than kept, I shall treat this as a bad promise, and break it whenever I shall be convinced that keeping it is adverse to the public interest; but I have not yet been so convinced. I have been shown a letter on this subject, supposed to be an able one, in which the writer expresses regret that my mind has not seemed to be definitely fixed on the question whether the seceded States, so called, are in the Union or out of it. It would perhaps add astonishment to his regret were he to learn that since I have found professed Union men endeavoring to make that question, I have purposely forborne any public expression upon it. As appears to me, that question has not been, nor yet is, a practically material one, and that any discussion of it, while it thus remains practically immaterial, could have no effect other than the mischievous one of dividing our friends. As yet, whatever it may hereafter become, that question is bad as the basis of a controversy, and good for nothing at all — a merely pernicious abstraction.

We all agree that the seceded States, so called, are out of their proper practical relation with the Union, and that the sole object of the government, civil and military, in regard to those States is to again get them into that proper practical relation. I believe that it is not only possible, but in fact easier, to do this without deciding or even considering whether these States have ever been out of the Union, than with it. Finding themselves safely at home, it would be utterly immaterial whether they had ever been abroad. Let us all join in doing the acts necessary to restoring the proper practical relations between these States and the Union, and each forever after innocently indulge his own opinion whether in doing the acts he brought the States from without into the Union, or only gave them proper assistance, they never having been out of it. The amount of constituency, so to speak, on which the new Louisiana government rests, would be more satisfactory to all if it contained 50,000, or 30,000, or even 20,000, instead of only about 12,000, as it does. It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.

Still, the question is not whether the Louisiana government, as it stands, is quite all that is desirable. The question is, will it be wiser to take it as it is and help to improve it, or to reject and disperse it! Can Louisiana be brought into proper practical relation with the Union sooner by sustaining or by discarding her new State government! Some twelve thousand voters in the heretofore slave State of Louisiana have sworn allegiance to the Union, assumed to be the rightful political power of the State, held elections, organized a State government, adopted a free-State constitution, giving the benefit of public schools equally to black and white, and empowering the legislature to confer the elective franchise upon the colored man. Their legislature has already voted to ratify the constitutional amendment recently passed by Congress, abolishing slavery throughout the nation. These 12,000 persons are thus fully committed to the Union and to perpetual freedom in the State —committed to the very things, and nearly all the things, the nation wants — and they ask the nation’s recognition and its assistance to make good their committal.

Now, if we reject and spurn them, we do our utmost to disorganize and disperse them. We, in effect, say to the white man: You are worthless or worse; we will neither help you, nor be helped by you. To the blacks we say: This cup of liberty which these, your old masters, hold to your lips we will dash from you, and leave you to the chances of gathering the spilled and scattered contents in some vague and undefined when, where, and how. If this course, discouraging and paralyzing both white and black, has any tendency to bring Louisiana into proper practical relations with the Union, I have so far been unable to perceive it. If, on the contrary, we recognize and sustain the new government of Louisiana, the converse of all this is made true. We encourage the hearts and nerve the arms of the 12,000 to adhere to their work, and argue for it, and proselyte for it, and fight for it, and feed it, and grow it, and ripen it to a complete success. The colored man, too, in seeing all united for him, is inspired with vigilance, and energy, and daring, to the same end. Grant that he desires the elective franchise, will he not attain it sooner by saving the already advanced steps toward it than by running backward over them! Concede that the new government of Louisiana is only to what it should be as the egg is to the fowl, we shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it.

Again, if we reject Louisiana we also reject one vote in favor of the proposed amendment to the national Constitution. To meet this proposition it has been argued that no more than three-fourths of those States which have not attempted secession are necessary to validly ratify the amendment. I do not commit myself against this further than to say that such a ratification would be questionable, and sure to be persistently questioned, while a ratification by three-fourths of all the States would be unquestioned and unquestionable. I repeat the question: Can Louisiana be brought into proper practical relation with the Union sooner by sustaining or by discarding her new State government! What has been said of Louisiana will apply generally to other States. And yet so great peculiarities pertain to each State, and such important and sudden changes occur in the same State, and withal so new and unprecedented is the whole case that no exclusive and inflexible plan can safely be prescribed as to details and collaterals. Such exclusive and inflexible plan would surely become a new entanglement. Important principles may and must be inflexible. In the present situation, as the phrase goes, it may be my duty to make some new announcement to the people of the South. I am considering, and shall not fail to act when satisfied that action will be proper.

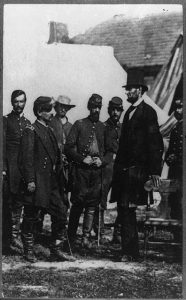

Abraham Lincoln on battlefield at Antietam, Maryland. Abraham Lincoln with, from left: Col. Alexander S. Webb, Chief of Staff, 5th Corps.; Gen. George B. McClellan; Scout Adams; Dr. Jonathan Letterman, Army Medical Director; an unidentified person; and standing behind Lincoln, Gen. Henry J. Hunt. September, 1862.

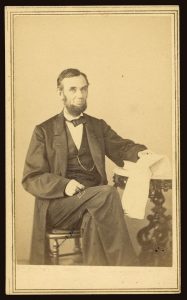

Abraham Lincoln Seated portrait, holding glasses and newspaper, Sunday, August 9, 1863

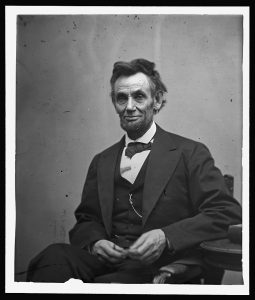

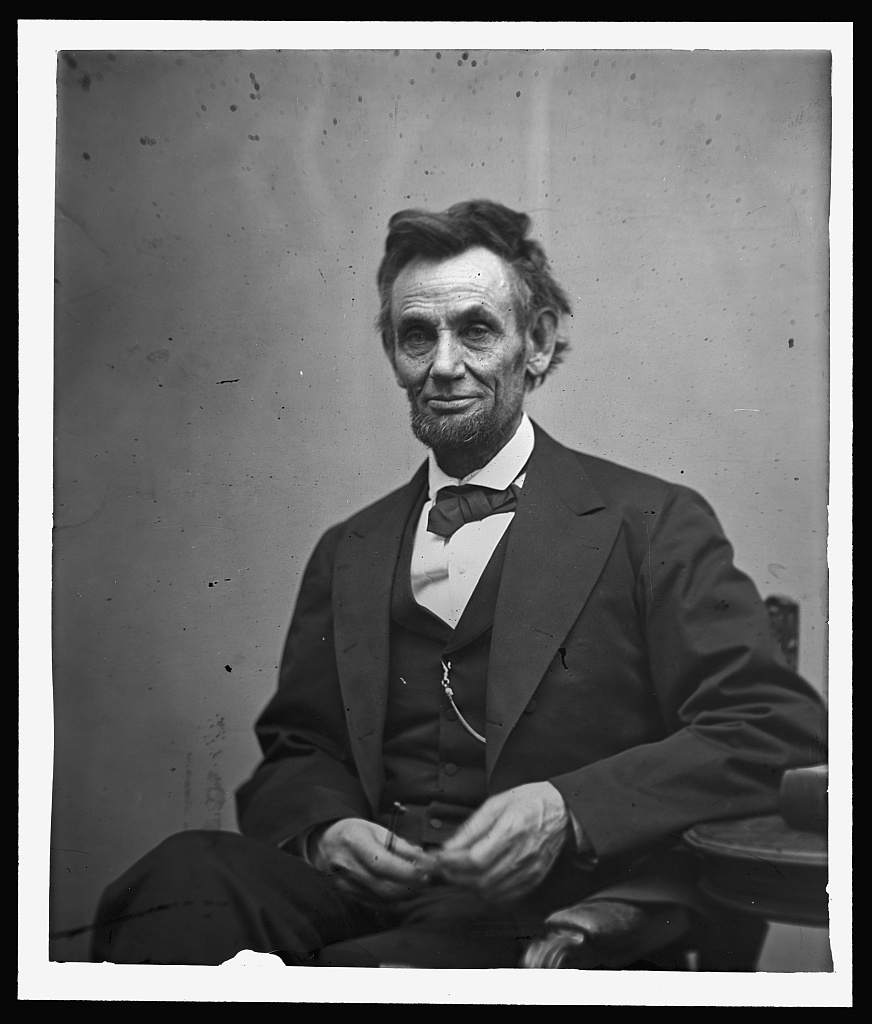

Abraham Lincoln, three-quarter length portrait, seated and holding his spectacles and a pencil. 1865 Feb. 5, 1965. photographer Alexander Gardner.

|

Abraham Lincoln Event Timeline |

|

|

11/06/1860 |

Election Day. |

|

12/05/1860 |

Electoral College votes cast. |

|

12/17/1860 |

Secession Convention meets in Columbia, South Carolina. |

|

12/20/1860 |

South Carolina secedes from the Union. |

|

1861 |

|

|

01/09/1861 |

Mississippi secedes followed by Alabama (1/11), Georgia (1/19), Louisiana (1/26), Texas 2/1). |

|

02/04/1861 – 03/16/1861 |

First session of Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America at Montgomery, Alabama. Adopts constitution on 02/09/1861. |

|

02/09/1861 |

Jefferson Davis is selected President of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States. |

|

02/13/1861 |

Electoral Votes tabulated by Congress. |

|

03/04/1861 |

Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address. |

|

03/16/1861 |

Message to the Senate on Royal Arbitration of American Boundary Lines. |

|

04/01/1861 |

Protective tariff system defined by Morrill Tariff takes effect. |

|

04/12/1861 |

Ft. Sumter, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, is shelled and surrenders the next day. |

|

04/15/1861 |

Proclamation 80 Calling Forth the Militia and Convening an Extra Session of Congress, Session to begin July 4, 1861. |

|

04/17/1861 |

Virginia secedes. |

|

04/19/1861 |

Proclamation 81- Declaring a Blockade of Ports in Rebellious States. |

|

04/20/1861 |

Robert E. Lee resigns his commission with the U.S. Army in order to “defend his native state” of Virginia. |

|

04/27/1861 |

Proclamation 82—Extension of Blockade to Ports of Additional States. |

|

05/03/1861 |

Proclamation 83- Increasing the Size of the Army and Navy. |

|

05/06/1861 |

Arkansas secedes. |

|

05/20/1861 |

North Carolina secedes. |

|

05/20/1861 |

Confederate capital relocated to Richmond, VA. |

|

05/24/1861 |

Union forces seize Arlington House, the residence of Robert E. Lee. |

|

06/08/1861 |

Tennessee secedes. |

|

06/20/1861 |

Western counties of Virginia break away from the state to form West Virginia and be recognized as a state in 1863. |

|

07/04/1861 |

In a Special Session Message, Lincoln reviews the events since his Inauguration and his decision to “call out the war power of the Government.” He calls for raising an army of at least 400,000. Argues forcefully against the idea that States have a right to withdraw from the Union. |

|

07/17/1861 |

Signs Appropriations for the Army for Fiscal Year 1862. This act supplemented funding for and expanding the Navy and Army. |

|

07/21/1861 |

First Battle of Bull Run, Manassas Junction, Virginia (Confederate victory). |

|

07/29/1861 |

Signs An Act for the Suppression of Rebellion authorizing the President to employ any military forces necessary “to enforce the faithful execution of the laws of the United States” against rebellions. |

|

08/05/1861 |

Signs a complex Revenue Act that includes among its provisions a three-percent tax on annual income about $800. |

|

08/06/1861 |

Signs an act that approves Lincoln’s emergency use of army and navy and militia. These orders are “in all respects legalized and made valid. . . as if they had been issued and done under the previous express authority and direction of the Congress of the United States.” |

|

08/06/1861 |

Signs Compensation Act which authorizing the seizing of any property used to support the insurrection, including slaves, providing a basis for freeing any escaped slaves. |

|

08/16/1861 |

Proclamation 86- Prohibiting Commercial Trade with States in Rebellion . |

|

10/24/1861 |

First transcontinental telegram sent from Sacramento, CA to Lincoln by the president of the Overland Telegraph Co. |

|

11/01/1861 |

McClellan named commanding General succeeding Wilfield Scott. |

|

12/03/1861 |

First Annual State of the Union Message. Lincoln discusses ways to encourage freeing of slaves and calls for a plan for colonization of the freed slaves. |

|

1862 |

|

|

01/27/1862 |

War Order #1 Directs that February 22 be a day for “general movement” of forces against the insurgents. |

|

02/14/1862 |

Executive Order relating to Political Prisoners directs release of prisoners suspected or accused of treason provided they agree to provide no aid or comfort to the enemies. |

|

02/20/1862 |

Lincoln’s son Willie dies at the White House at the age of 11. |

|

03/06/1862 |

Recommends to Congress a program of compensated emancipation of slaves. |

|

03/08/0862 – 03/09/1862 |

First battle of ironclad warships; demonstrated the importance of ironclads, and eventually kept the Confederate ship confined in a body of water known as Hampton Roads. |

|

03/13/1862 |

Signs Act prohibiting the return by military forces of escaped slaves. |

|

04/06/1862 – 04/07/1862 |

Ulysses S. Grant wins major Union victory at Battle of Shiloh in western Tennessee. |

|

04/16/1862 |

Signs “Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service of Labor in the District of Columbia,” freeing slaves in the District and compensating their owners up to $300 provided the owner swears an oath of allegiance to the Government of the United States. Appropriates $1 Million for the program and $100,000 to “aid in the colonization and settlement of such free persons of African descent now residing in said District.” |

|

05/12/1862 |

Proclamation 89—Termination of Blockade of Beaufort, North Carolina, Port Royal, South Carolina, and New Orleans, Louisiana. |

|

05/20/1862 |

Signs Homestead Act allowing settlers to acquire up to 160 acres of public land. |

|

05/25/1862 |

Executive Order- Taking Military Possession of Railroads. |

|

06/01/1862 |

General Robert E. Lee becomes commander of Army of Northern Virginia replacing General Joseph Johnson who had been wounded in battle. |

|

06/19/1862 |

Signs Act eliminating slavery in any Territories of the United States. |

|

06/26/1862 |

Order Constituting the [Union] Army of Virginia. |

|

07/02/1862 |

Signs Morill Act donating public land to be used to support colleges “for agriculture and the mechanic arts.” |

|

07/04/1862 |

Message to Congress Proposing an Act of Compensated Emancipation. |

|

07/17/1862 |

Second Confiscation Act declaring that slaves owned by anyone participating in rebellion will be made free; seeks to seize property of Confederate leaders; specifies that escaped slaves are to be set free; allows the President to “employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion.” |

|

07/17/1862 |

Signs Act amending the Act calling forth the Militia. Includes provision freeing any slave serving in the Militia together with his mother, his wife and his children. |

|

08/17/1862 |

Beginning of “Dakota War” in the State of Minnesota. Dakota warriors angry about their conditions attacked white settlers. Eventually over 600 settlers and soliders died as well as 75-100 Dakota. |

|

08/22/1862 |

Letter to Horace Greely published in New York Times, August 24; “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.” |

|

08/30/1862 – 08/31/1862 |

Second Battle of Bull Run (Manassas, VA) and a second Confederate victory. |

|

09/17/1862 |

Battle of Antietam (Maryland); bloody battle ends Lee’s invasion of the North. |

|

09/22/1862 |

Proclamation 93—Declaring the Objectives of the War Including Emancipation of Slaves in Rebellious States on January 1, 1863 (Emancipation Proclamation). |

|

12/01/1862 |

State of the Union Message. Discusses prospects for colonization of “free Americans of African descent.” Observes that “Indian tribes upon our frontiers have during the past year manifested a spirit of insubordination. . . “ The Sioux Indians attacked settlements “with extreme ferocity.” Proposes a constitutional amendment for compensated abolition of slavery. |

|

12/11/1862 |

Message to the Senate Responding to the Resolution Regarding Indian Barbarities in the State of Minnesota. Reports that he commuted the death sentences of all convicted in the “Dakota Wars” except for those proven to have participated in massacres as opposed to battles. |

|

12/13/1862 |

Battle of Fredericksburg (VA), is a grave defeat for the Union Army. |

|

12/31/1862 |

Signs Act admitting West Virginia to the Union once a vote of the people certifies the choice and the President issues a proclamation. |

|

1863 |

|

|

01/01/1863 |

Proclamation 95—Regarding the Status of Slaves in States Engaged in Rebellion Against the United States [Emancipation Proclamation]. |

|

02/24/1863 |

Territory of Arizona established. |

|

02/25/1863 |

Signs the National Banking Act, creates a system for national banking; system of national currency; creates the office of Comptroller of the Currency. |

|

03/03/1863 |

Territory of Idaho established. |

|

03/03/1863 |

Incorporation of the National Academy of Sciences. |

|

03/03/1863 |

Signs Habeas Corpus Act authorizing the President, during the present rebellion to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus “whenever, in his judgment the public safety may require it.” |

|

04/20/1863 |

Proclamation 100, Admitting West Virginia to the Union. (Admission takes effect 60 days later.) |

|

05/19/1863 |

General Grant opens his assault on Vicksburg (MS) in an effort to wrest control of the Mississippi River from the Confederates. |

|

05/23/1863 |

The War Department issues General Order 143, creating a Bureau devoted to the organizing of Colored Troops. |

|

06/20/1863 |

West Virginia admitted as a state. |

|

07/01/1863 – 07/03/1862 |

Battle of Gettysburg. Confederate invasion of the North fails after a fierce battle with over 7,000 dead and 27,000 wounded. |

|

07/04/1863 |

Confederate troops surrender at Vicksburg (MS) after a 47 day siege. |

|

07/13/1862 – 07/16/1863 |

New York City draft riots. Protests against the draft degenerated into a anti-Black race riot leaving around 120 dead. |

|

07/30/1863 |

Executive Order directs equal retaliation against Southern prisoners for instances of execution or enslavement of Northern prisoners by the South. |

|

08/26/1863 |

Lincoln letter to James C. Conkling defending his policies on emancipation against criticism from Union supporters. |

|

09/15/1863 |

Proclamation 104- Suspending the Writ of Habeas Corpus Throughout the United States. |

|

10/17/1863 |

Proclamation 107—Call for 300,000 Volunteers. |

|

11/19/1863 |

Gettysburg Address. At the dedication of a cemetery for the battle dead. |

|

12/08/1863 |

Third Annual State of the Union Message. |

|

12/08/1863 |

Proclamation 108—Amnesty and Reconstruction. Proposes lenient terms for former Confederates who accept prior Proclamations regarding slavery. |

|

1864 |

|

|

02/24/1864 |

Act authorizes President to establish quotas for volunteers as needed, and if insufficient volunteers, draft authorized. |

|

03/10/1864 |

By Executive Order designates Ulysses Grant as commander of the armies of the United States. |

|

03/26/1864 |

Proclamation 111 limits amnesty to individuals not already in custody (prisoners) or under bonds or on patrol. |

|

04/04/1864 |

Letter to Albert G. Hodges. Lincoln explains and defends the evolution of his thinking about emancipation. “I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation.” |

|

04/08/1864 |

The Senate passes joint resolution to adopt the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, ending slavery. |

|

04/18/1864 |

Address at Sanitary Fair in Baltimore: A Lecture on Liberty. Addresses reports of massacre of Union troops imprisoned at Fort Pillow, Tennessee (see proclamation of 07/30/1863) |

|

05/18/1864 |

Executive order for Arrest and Imprisonment of Irresponsible Newspaper Reporters and Editors. |

|

05/26/1864 |

Signs Act establishing Territory of Montana. |

|

06/07/1864 |

Lincoln nominated for President at Union National Convention. |

|

06/16/1864 |

Address at a Sanitary Fair in Philadelphia. |

|

06/27/1864 |

Lincoln Letter Accepting the Presidential Nomination. |

|

06/28/1864 |

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 repealed. |

|

07/04/1864 |

Pocket Veto of Wade-Davis Reconstruction bill (see 07/08/1864). |

|

07/05/1864 |

Proclamation 113 Declares Martial Law and suspends Habeas Corpus in Kentucky. Acts pursuant to Act of 03/03/1863 (above). |

|

07/08/1864 |

Proclamation 115 explains the pocket veto of the Wade Davis Reconstruction bill. |

|

07/09/1864 – 07/22/1864 |

Exchange of letters with Horace Greeley about possibility of peace negotiations in Niagara Falls. |

|

07/18/1864 |

In Proclamation 116, calls for 500,000 volunteers pursuant to a law that authorizes him to institute a draft in areas where quotas are not met. |

|

08/15/1864 |

Interview with John T. Mills. “Abandon all the posts now garrisoned by black men, take one hundred and fifty thousand men from our side and put them in the battle-field or corn-field against us, and we would be compelled to abandon the war in three weeks.” |

|

09/03/1864 |

Executive Order Tendering Thanks to Major-General William T. Sherman [upon capture of Atlanta, Georgia on September 2]. Also directs a celebration of Sherman’s successes at military posts around the country by Executive Order. |

|

10/31/1864 |

Proclamation 119—Admitting State of Nevada Into the Union. |

|

11/08/1864 |

Election Day. Lincoln handily defeats George McClellan. |

|

12/06/1864 |

Fourth Annual State of the Union Message. |

|

12/19/1864 |

Proclamation 121—Calling for 300,000 Volunteers. |

|

1865 |

|

|

01/31/1865 |

House of Representatives passes resolution proposing the 13th Amendment. |

|

02/01/1865 |

Signs resolution submitting to the states the 13th Amendment to the Constitution; Amendment submitted to the states for ratification. |

|

02/03/1865 |

Hampton Roads Peace Conference between Lincoln, Secretary of State Seward and two members of the Confederate Cabinet. |

|

02/09/1865 |

Message of Reply to a Committee of Congress Reporting the Result of the Electoral Vote Count |

|

02-10-1865 |

Message to the House of Representatives Containing a Chronologic Review of Peace Proposals [to end the Civil War]. |

|

03/03/1865 |

Signs Act Creating a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees. |

|

03/04/1865 |

Second Inaugural Address. “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” |

|

03/11/1865 |

Proclamation 124—Offering Pardon to Deserters. |

|

03/14/1865 |

Executive Order—Ordering the Arrest and Designation as Prisoners of War all Persons engaged in intercourse or trade with the Insurgents by sea. |

|

03/17/1865 |

Proclamation 125—Ordering the Arrest and Prosecution of those Furnishing arms to Hostile Indians. |

|

03/17/1865 |

Address to an Indiana Regiment. “While I have often said that all men ought to be free, yet would I allow those colored persons to be slaves who want to be, and next to them those white people who argue in favor of making other people slaves.” |

|

03/27/1865 |

Executive Order—Ordering the Raising of the Flag and other Commemorations at Fort Sumter. |

|

04/03/1865 |

Union troops occupy Petersburg and Richmond. |

|

04/04/1865 |

Lincoln visits Richmond. |

|

04/09/1865 |

Lee surrenders Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House but other Confederate Generals continue to fight. |

|

04/11/1865 |

Final public Address to a crowd on the White House lawn. |

|

04/15/1865 |

Lincoln assassination. |

Sources:

Images from Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.. John G. Nicolay and John Hay, “Abraham Lincoln: Complete Works, Comprising His Speeches, Letters, State Papers, and Miscellaneous Writings”, vol. II, 1894. Abraham Lincoln, The President’s Last Public Address Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. Abraham Lincoln Event Timeline Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project