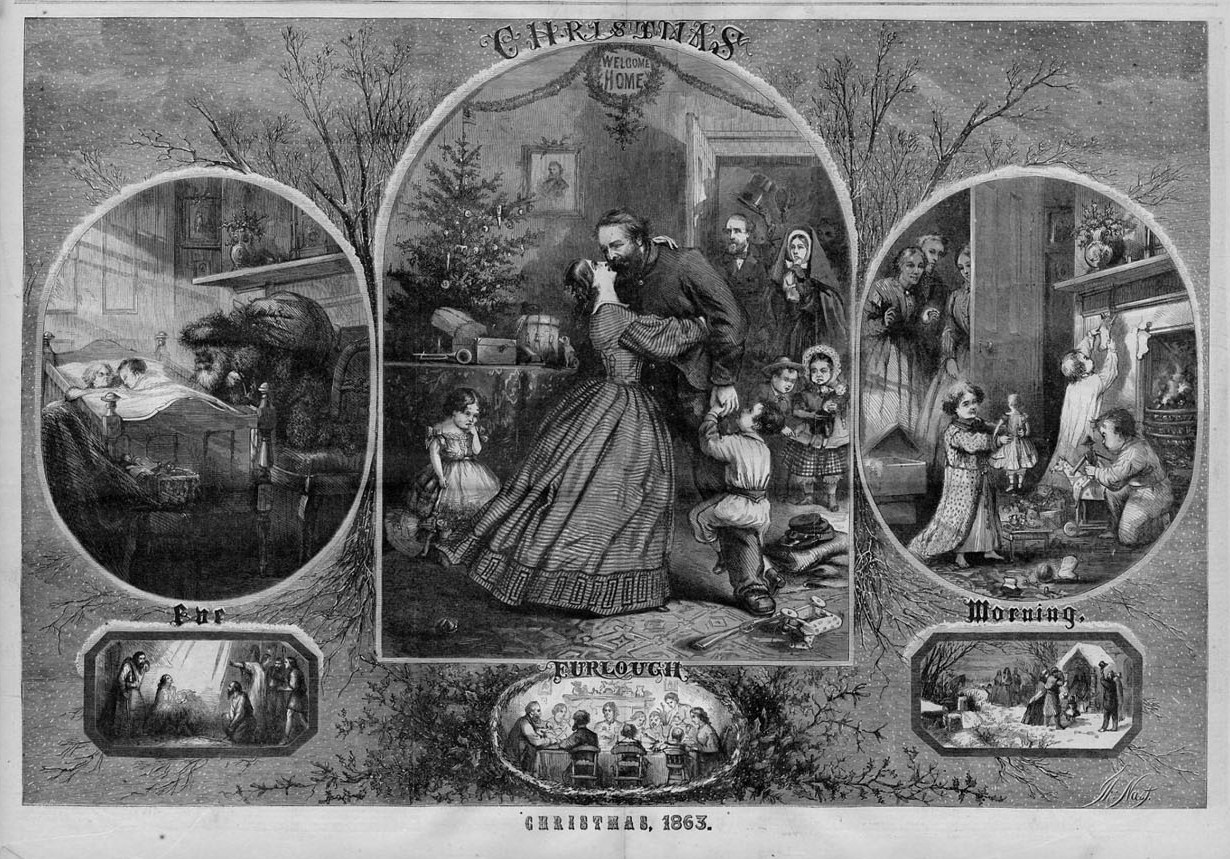

“I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” is a Christmas carol based on the 1863 poem “Christmas Bells” by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The song tells of the narrator’s despair, upon hearing Christmas bells, that “hate is strong and mocks the song of peace on earth, good will to men”. The carol concludes with the bells carrying renewed hope for peace among men.

Longfellow first wrote the poem on Christmas Day in 1863. “Christmas Bells” was first published in February 1865, in a juvenile magazine. References to the Civil War are prevalent in some of the verses that are not commonly sung.

It was not until 1872 that the poem is known to have been set to music. The English organist, John Baptiste Calkin, used the poem in a processional accompanied with a melody he previously used as early as 1848. The Calkin version of the carol was long the standard. Less commonly, the poem has also been set to Joseph Mainzer’s composition “Mainzer” (1845).

Christmas 1863

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,And wild and sweet

The words repeatOf peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all ChristendomHad rolled along

The unbroken songOf peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till, ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,A voice, a chime,

A chant sublimeOf peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,And with the sound

The carols drownedOf peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,And made forlorn

The households bornOf peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said:

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the songOf peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,With peace on earth, good-will to men!”

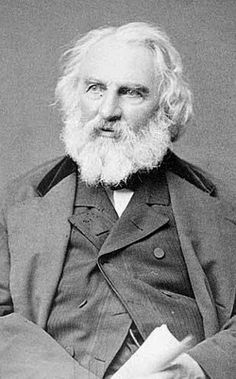

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

(1807-1882) Portland, Maine

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine—then still part of Massachusetts—on February 27, 1807, the second son in a family of eight children. His mother, Zilpah Wadsworth, was the daughter of a Revolutionary War hero. His father, Stephen Longfellow, was a prominent Portland lawyer and later a member of Congress.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine—then still part of Massachusetts—on February 27, 1807, the second son in a family of eight children. His mother, Zilpah Wadsworth, was the daughter of a Revolutionary War hero. His father, Stephen Longfellow, was a prominent Portland lawyer and later a member of Congress.

Henry was a dreamy boy who loved to read. He heard sailors speaking Spanish, French and German in the Portland streets and liked stories set in foreign places: The Arabian Nights, Robinson Crusoe, and the plays of Shakespeare.

After graduating from Bowdoin College, Longfellow studied modern languages in Europe for three years, then returned to Bowdoin to teach them. In 1831 he married Mary Storer Potter of Portland, a former classmate, and soon published his first book, a description of his travels called Outre Mer (“Overseas”). But in November 1835, during a second trip to Europe, Longfellow’s life was shaken when his wife died during a miscarriage. The young teacher spent a grief-stricken year in Germany and Switzerland.

Longfellow took a position at Harvard in 1836. Three years later, at the age of thirty-two, he published his first collection of poems, Voices of the Night, followed in 1841 by Ballads and Other Poems. Many of these poems (“A Psalm of Life,” for example) showed people triumphing over adversity, and in a struggling young nation that theme was inspiring. Both books were very popular, but Longfellow’s growing duties as a professor left him little time to write more. In addition, Frances Appleton, a young woman from Boston, had refused his proposal of marriage.

Frances finally accepted his proposal the following spring, ushering in the happiest eighteen years of Longfellow’s life. The couple had six children, five of whom lived to adulthood, and the marriage gave him new confidence. In 1847, he published Evangeline, a book-length poem about what would now be called “ethnic cleansing.” The poem takes place as the British drive the French from Nova Scotia, and two lovers are parted, only to find each other years later when the man is about to die.

In 1854, Longfellow decided to quit teaching to devote all his time to poetry. He published Hiawatha, a long poem about Native American life, and The Courtship of Miles Standish and Other Poems. Both books were immensely successful, but Longfellow was now preoccupied with national events. With the country moving toward civil war, he wrote “Paul Revere’s Ride,” a call for courage in the coming conflict.

A few months after the war began in 1861, Frances Longfellow was sealing an envelope with wax when her dress caught fire. Despite her husband’s desperate attempts to save her, she died the next day. Profoundly saddened, Longfellow published nothing for the next two years. He found comfort in his family and in reading Dante’s Divine Comedy. (Later, he produced its first American translation.) Tales of a Wayside Inn,<> largely written before his wife’s death, was published in 1863.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the poet was fifty-eight. His most important work was finished, but his fame kept growing. In London alone, twenty-four different companies were publishing his work. His poems were popular throughout the English-speaking world, and they were widely translated, making him the most famous American of his day. His admirers included Abraham Lincoln, Charles Dickens, and Charles Baudelaire.

From 1866 to 1880, Longfellow published seven more books of poetry, and his seventy-fifth birthday in 1882 was celebrated across the country. But his health was failing, and he died the following month, on March 24. When Walt Whitman heard of the poet’s death, he wrote that, while Longfellow’s work “brings nothing offensive or new, does not deal hard blows,” he was the sort of bard most needed in a materialistic age: “He comes as the poet of melancholy, courtesy, deference—poet of all sympathetic gentleness—and universal poet of women and young people. I should have to think long if I were ask’d to name the man who has done more and in more valuable directions, for America.”

Selected Bibliography

Poetry

Aftermath (1873)

Ballads and Other Poems (1841)

Christus: A Mystery (1872)

Evangeline (1847)

Flower-de-Luce (1867)

Household Poems (1863)

Keramos and Other Poems (1878)

Poems on Slavery (1842)

Tales of a Wayside Inn (1863)

The Belfry of Bruges and Other Poems (1845)

The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858)

The Golden Legend (1851)

The Masque of Pandora and Other Poems (1875)

The Seaside and Fireside (1849)

The Song of Hiawatha (1855)

Three Books of Song (1872)

Ultima Thule (1880)

Voices of the Night (1839)

Prose

The New England Tragedies (1868)

Drama

The Spanish Student (1843)

Essays

Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimmage Beyond the Sea (1835)

Fiction

Hyperion: A Romance (1839)

Kavanagh: A Tale (1849)

Poetry in Translation

The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri (1867)

Source: The Academy of American Poets