Columbia (OV-102), the first of NASA’s orbiter fleet, was delivered to Kennedy Space Center in March 1979. Columbia initiated the Space Shuttle flight program when it lifted off Pad A in the Launch Complex 39 area at KSC on April 12, 1981. It proved the operational concept of a winged, reusable spaceship by successfully completing the Orbital Flight Test Program – missions STS-1 through STS-4.

Other, achievements for Columbia included the recovery of the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) satellite from orbit during mission STS-32 in January 1990, and the STS-40 Spacelab Life Sciences mission in June 1991 – the first manned Spacelab mission totally dedicated to human medical research.

Columbia was destroyed over east Texas on its landing descent to Kennedy Space Center on Feb. 1, 2003, at 8:59 a.m. EST at the conclusion of a microgravity research mission, STS-107.

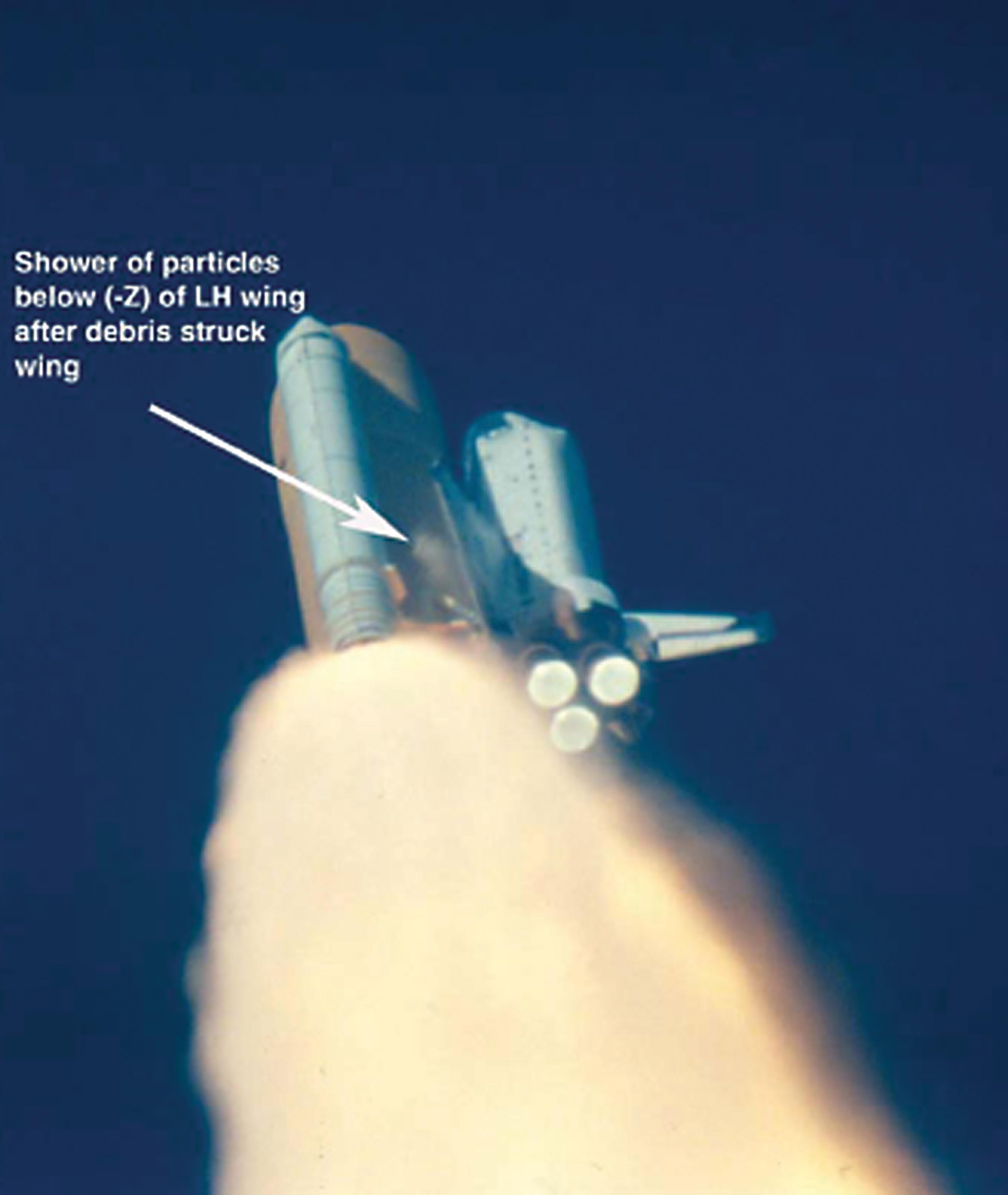

The Columbia STS-107 mission lifted off on January 16, 2003, for a 17-day science mission featuring numerous microgravity experiments. Upon reentering the atmosphere on February 1, 2003, the Columbia orbiter suffered a catastrophic failure due to a breach that occurred during launch when falling foam from the External Tank struck the Reinforced Carbon Carbon panels on the underside of the left wing. The orbiter and its seven crewmembers (Rick D. Husband, William C. McCool, David Brown, Laurel Blair Salton Clark, Michael P. Anderson, Ilan Ramon, and Kalpana Chawla) were lost approximately 15 minutes before Columbia was scheduled to touch down at Kennedy Space Center.

An investigation board determined that the large piece of foam from the shuttle’s external tank and breached the spacecraft wing. This problem with foam had been known for years, and NASA came under intense scrutiny in Congress and in the media for allowing the situation to continue. Space Shuttle fleet was grounded for more than two years while safety measures were added, including procedures to deal with catastrophic cabin depressurization, better crew restraints, and an automated parachute system.

The Columbia mission was the second space shuttle disaster after Challenger, which saw a catastrophic failure during launch in 1986. The Columbia disaster directly led to the retirement of the space shuttle fleet in 2011; NASA is developing a successor commercial crew program that will bring astronauts to the space station no earlier than 2018.

Columbia was named after a small sailing vessel that operated out of Boston in 1792 and explored the mouth of the Columbia River. One of the first ships of the U.S. Navy to circumnavigate the globe was named Columbia. The command module for the Apollo 11 lunar mission was also named Columbia.

On April 12, 1981, a bright white Columbia roared into a deep blue sky as the nation’s first reusable Space Shuttle. Named after the first American ocean vessel to circle the globe and the command module for the Apollo 11 Moon landing, Columbia continued this heritage of intrepid exploration. The heaviest of NASA’s orbiters, Columbia weighed too much and lacked the necessary equipment to assist with assembly of the International Space Station. Despite its limitations, the orbiter’s legacy is one of groundbreaking scientific research and notable “firsts” in space flight.

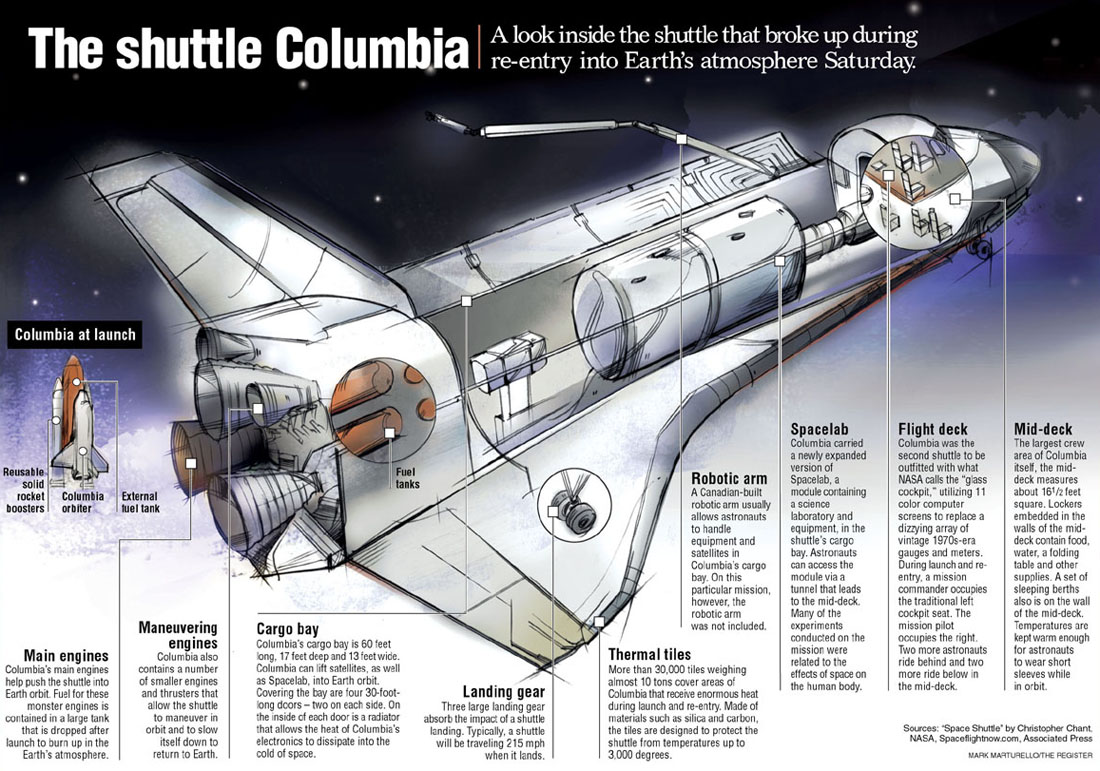

Space Shuttle mission STS-9, launched in late November 1983, was the maiden flight for Spacelab. Designed to be a space-based science lab, Spacelab was installed inside the orbiter’s cargo bay. Spacelab featured an enclosed crew work module connected to an outside payload pallet, which could be mounted with various instruments and experiments. From inside the lab, astronauts worked with the experiments on the pallet and within the crew module itself. The lab would go on to fly aboard the rest of the fleet, playing host throughout its accomplished lifetime to unprecedented research in astronomy, biology and other sciences. Spacelab ultimately finished where its career began; its 16th and final mission was hoisted into space aboard Columbia in 1998.

In addition to Columbia’s STS-1 flight and Spacelab, the orbiter was also the stage for many other remarkable firsts. Germany’s Dr. Ulf Merbold became the first European Space Agency astronaut when he flew aboard 1983’s STS-9. The Japanese Space Agency and STS-65’s Chiaki Mukai entered history as the first Japanese woman to fly in space in 1994. In a display of national pride, the crew of STS-73 even “threw” the ceremonial first pitch for game five of the 1995 baseball World Series, marking the first time the pitcher was not only outside of the stadium, but out of this world.

Perhaps Columbia’s crowning achievement was the deployment of the gleaming Chandra X-ray Observatory in July 1999. Carried into space inside the orbiter’s payload bay, the slender and elegant Chandra telescope was released on July 23. Still in flight today, the X-ray telescope specializes in viewing deep space objects and finding the answers to astronomy’s most fundamental questions.

Columbia and its crew were tragically lost during STS-107 in 2003. As the Space Shuttle lifted off from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on January 16, a small portion of foam broke away from the orange external fuel tank and struck the orbiter’s left wing. The resulting damage created a hole in the wing’s leading edge, which caused the vehicle to break apart during reentry to Earth’s atmosphere on February 1.

Construction Milestones

| July 26, 1972 | Contract Award |

| March 25, 1975 | Start long lead fabrication aft fuselage |

| November 17, 1975 | Start long-lead fabrication of crew module |

| June 28, 1976 | Start assembly of crew module |

| September 13, 1976 | Start structural assembly of aft-fuselage |

| December 13, 1976 | Start assembly upper forward fuselage |

| January 3, 1977 | Start assembly vertical stabilizer |

| August 26, 1977 | Wings arrive at Palmdale from Grumman |

| October 28, 1977 | Lower forward fuselage on dock, Palmdale |

| November 7, 1977 | Start of Final Assembly |

| February 24, 1978 | Body flap on dock, Palmdale |

| April 28, 1978 | Forward payload bay doors on dock, Palmdale |

| May 26,1978 | Upper forward fuselage mate |

| July 7, 1978 | Complete mate forward and aft payload bay doors |

| September 11, 1978 | Complete forward RCS |

| February 3, 1979 | Complete combined systems test, Palmdale |

| February 16, 1979 | Airlock on dock, Palmdale |

| March 5, 1979 | Complete postcheckout |

| March 8, 1979 | Closeout inspection, Final Acceptance Palmdale |

| March 8, 1979 | Rollout from Palmdale to Dryden (38 miles) |

| March 12, 1979 | Overland transport from Palmdale to Edwards |

| March 20, 1979 | SCA Ferry Flight from DFRF to Bigs AFB, Texas |

| March 22, 1979 | SCA Ferry flight from Bigs AFB to Kelly AFB, Texas |

| March 24, 1979 | SCA Ferry flight from Kelly AFB to Eglin AFB, Florida |

| March 24, 1979 | SCA Ferry flight from Eglin, AFB to KSC |

| November 3, 1979 | Auxiliary Power Unit hot fire tests, OPF KSC |

| December 16, 1979 | Orbiter integrated test start, KSC |

| January 14, 1980 | Orbiter integrated test complete, KSC |

| February 20, 1981 | Flight Readiness Firing |

| April 12, 1981 | First Flight (STS-1) |

The Hubble Space Telescope, in the grasp of space shuttle Columbia’s robotic arm, is captured by the STS-109 crew members on flight day three. Moments later, the giant telescope was locked down in the shuttle’s cargo bay, where it went on to remain as the crew members performed five spacewalks in the following week to service and upgrade it.

Barely visible within the Hubble Space Telescope’s heavily shadowed shroud doors, astronauts John M. Grunsfeld (left) and Richard M. Linnehan participate in the final spacewalk of the STS-109 mission. The crew of the space shuttle Columbia completed the last of its five ambitious spacewalks early on March 8, 2002, with the successful installation of an experimental cooling system for Hubble’s Near-Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer.

Upgrades and Features

Columbia is commonly referred to as OV-102, for Orbiter Vehicle-102. The orbiter weighed 178,000 pounds with its main engines installed.

Columbia was the first orbiter to undergo the scheduled inspection and retrofit program. In 1991, Columbia returned to its birthplace at Rockwell International’s Palmdale, Calif., assembly plant. The spacecraft underwent approximately 50 upgrades there, including the addition of carbon brakes and a drag chute, improved nose wheel steering, removal of instrumentation used during the test phase of the orbiter, and an enhancement of its Thermal Protection System. The orbiter returned to Florida in February 1992 to begin processing for mission STS-50, launching in June of that year.

In 1994, Columbia was transported back to Palmdale for its first major tear-down and overhaul, known as the Orbiter Maintenance Down Period (OMDP). This overhaul typically lasts one year or longer and leaves the vehicle in “like-new” condition.

Its second OMDP came in 1999, when workers performed more than 100 modifications on the vehicle. The orbiter’s most impressive upgrade likely was the installation of a state-of-the-art, Multi-functional Electronic Display System (MEDS), or “glass cockpit.” The MEDS replaced traditional instrument dials and gauges with small, computerized video screens. The new system improved crew interaction with the orbiter during flight and reduced maintenance costs by eliminating the outdated and tricky electromechanical displays.

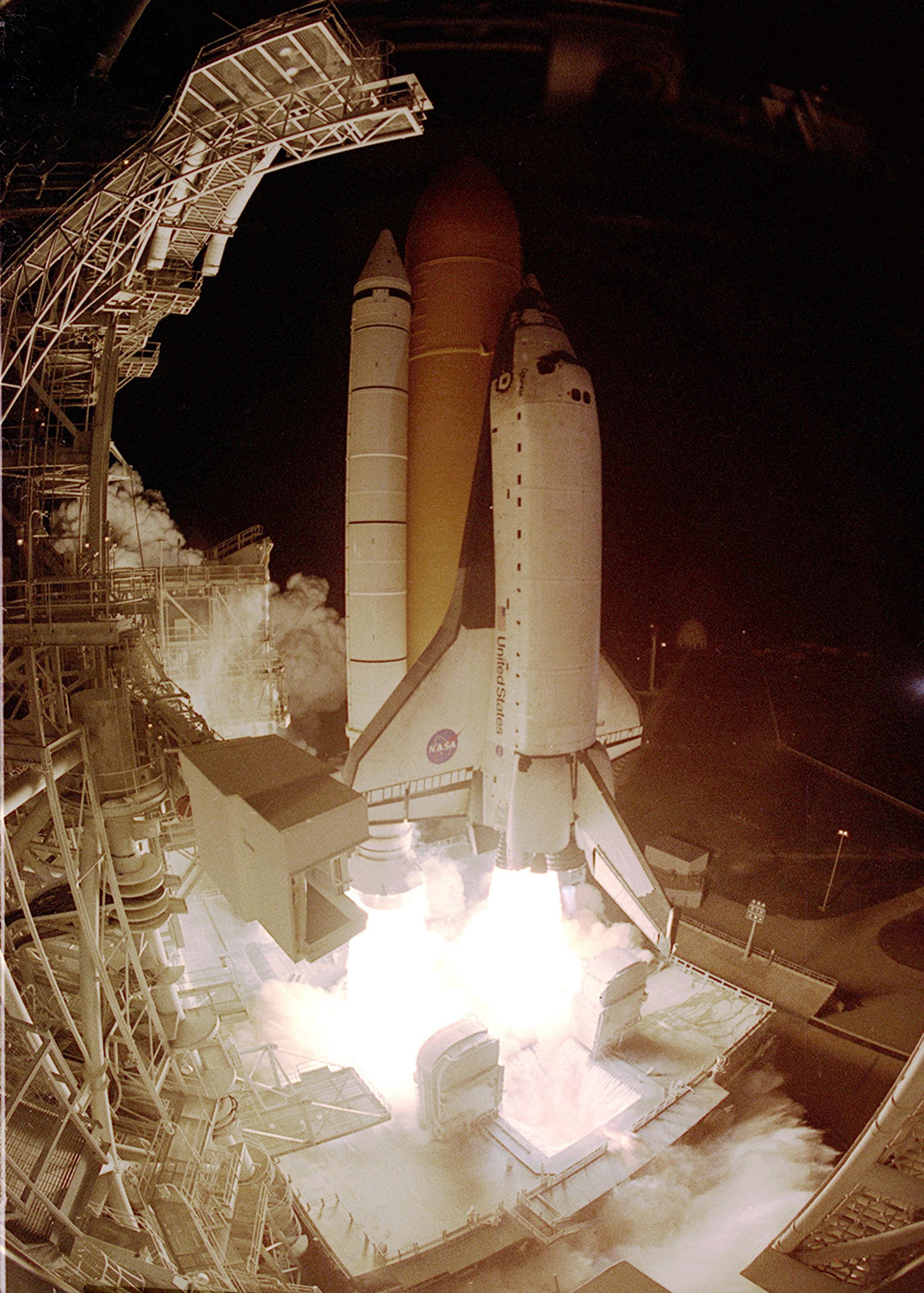

Trees and shrubs are silhouetted on the near bank by the brilliant exhaust of Space Shuttle Columbia as it hurtles into the pre-dawn sky on mission STS-109. Liftoff of Columbia occurred at 6:22:02:08 a.m. EST (11:22:02:08 GMT). This was the 27th flight of the vehicle and 108th in the history of the Shuttle program. The goal of the mission is the maintenance and upgrade of the Hubble Space Telescope, to be carried out in five spacewalks. The crew comprises Commander Scott D. Altman, Pilot Duane G. Carey, Payload Commander John M. Grunsfeld, and Mission Specialists Nancy Jane Currie, Richard M. Linnehan, James H. Newman and Michael J. Massimino. After the 11-day mission, Columbia is expected to return to KSC March 12 about 4:35 a.m. EST (09:35 GMT)

A fish-eye lens gives a different perspective to the launch of Space Shuttle Columbia on mission STS-109. Torrents of water spread over the Mobile Launcher Platform from 12-foot rainbirds and into the flame trench as part of the sound suppression system. Acoustical levels reach their peak when the Space Shuttle is about 300 feet above the MLP. At left of the Shuttle is the Fixed Service Structure with the Orbiter Access Arm and White Room, seen in the foreground. Liftoff of Columbia occurred at 6:22:02:08 a.m. EST (11:22:02:08 GMT). This was the 27th flight of the vehicle and 108th in the history of the Shuttle program. The goal of the mission is the maintenance and upgrade of the Hubble Space Telescope, to be carried out in five spacewalks. The crew comprises Commander Scott D. Altman, Pilot Duane G. Carey, Payload Commander John M. Grunsfeld, and Mission Specialists Nancy Jane Currie, Richard M. Linnehan, James H. Newman and Michael J. Massimino. After the 11-day mission, Columbia is expected to return to KSC March 12 about 4:35 a.m. EST (09:35 GMT)

At the Shuttle Landing Facility, egrets along the runway take flight as the orbiter Columbia leaves Kennedy Space Center on the back of a Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft on a ferry flight to Palmdale, Calif. Columbia, the oldest of four orbiters in NASA’s fleet, will undergo extensive inspections and modifications in Boeing’s Orbiter Assembly Facility during a nine-month orbiter maintenance down period (OMDP), the second in its history. Orbiters are periodically removed from flight operations for an OMDP. Columbia’s first was in 1994. Along with more than 100 modifications on the vehicle, Columbia will be the second orbiter to be outfitted with the multifunctional electronic display system, or “glass cockpit.” Columbia is expected to return to KSC in July 2000

NASA Space Shuttle Columbia hitches ride on a special 747 carrier aircraft for the flight from Palmdale, Calif., to Kennedy Space Center, Fla

Final Mission

Space Shuttle Columbia is being moved to the Vehicle Assembly Building where processing will continue for the flight of mission STS-107. Launch is now targeted for no earlier than Jan. 16, 2003. The STS-107 mission will be dedicated to microgravity research. The payloads include the Hitchhiker Bridge, a carrier for the Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research (FREESTAR) incorporating eight high priority secondary attached Shuttle experiments, and the SHI Research Double Module (SHI/RDM), also known as SPACEHAB.

Space Shuttle Columbia is backed out of its Orbiter Processing Facility bay as it starts its move to the Vehicle Assembly Building. The orbiter is being prepared to fly on mission STS-107 now targeted for no earlier than Jan. 16, 2003. The STS-107 mission will be dedicated to microgravity research. The payloads include the Hitchhiker Bridge, a carrier for the Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research (FREESTAR) incorporating eight high priority secondary attached Shuttle experiments, and the SHI Research Double Module (SHI/RDM), also known as SPACEHAB.

Space Shuttle Columbia rolls towards Launch Pad 39A, sitting atop the Mobile Launcher Platform, which in turn is carried by the crawler-transporter underneath. The STS-107 research mission comprises experiments ranging from material sciences to life sciences (many rats), plus the Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research (FREESTAR) that incorporates eight high priority secondary attached shuttle experiments. Mission STS-107 is scheduled to launch Jan. 16, 2003.

Space Shuttle Columbia, atop the Mobile Launcher Platform, approaches the top of Launch Pad 39A where it will undergo preparations for launch. The STS-107 research mission comprises experiments ranging from material sciences to life sciences, plus the Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research (FREESTAR) that incorporates eight high priority secondary attached shuttle experiments. Mission STS-107 is scheduled to launch Jan. 16, 2003.

Space Shuttle Columbia sits on Launch Pad 39A, atop the Mobile Launcher Platform. The STS-107 research mission comprises experiments ranging from material sciences to life sciences, plus the Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research (FREESTAR) that incorporates eight high priority secondary attached shuttle experiments. Mission STS-107 is scheduled to launch Jan. 16, 2003.

The late afternoon sun highlights the external tank and solid rocket booster on Space Shuttle Columbia after rollback of the Rotating Service Structure on Launch Pad 39A. Visible are the orbiter access arm with the White Room extended to Columbia’s cockpit, and at the top, the gaseous oxygen vent arm and cap, called the “beanie cap.” Columbia is scheduled for launch Jan. 16 at 10:39 a.m. EST on mission STS-107, a research mission.

Seeming to be perched on twin columns of fire, Space Shuttle Columbia leaps off Launch Pad 39A and races toward space on missions STS-107. Following a flawless and uneventful countdown, liftoff occurred on-time at 10:39 a.m. EST. The 16-day research mission will include FREESTAR (Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research) and the SHI Research Double Module (SHI/RDM), known as SPACEHAB. Experiments on the module range from material sciences to life sciences.. Landing of Columbia is scheduled at about 8:53 a.m. EST on Saturday, Feb. 1. This mission is the first Shuttle mission of 2003. Mission STS-107 is the 28th flight of the orbiter Columbia and the 113th flight overall in NASA’s Space Shuttle program. [Photo courtesy of Scott Andrews]

Spewing flames and billowing clouds of smoke across Launch Pad 39A, Space Shuttle Columbia roars toward space on mission STS-107. Following a flawless and uneventful countdown, liftoff occurred on-time at 10:39 a.m. EST. The 16-day research mission will include FREESTAR (Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research) and the SHI Research Double Module (SHI/RDM), known as SPACEHAB. Experiments on the module range from material sciences to life sciences.. Landing of Columbia is scheduled at about 8:53 a.m. EST on Saturday, Feb. 1. This mission is the first Shuttle mission of 2003. Mission STS-107 is the 28th flight of the orbiter Columbia and the 113th flight overall in NASA’s Space Shuttle program. [Photo courtesy of Scott Andrews]

Silhouetted against the blue Atlantic Ocean, Space Shuttle Columbia breaks free of the launch pad as it roars toward space on mission STS-107. Following a flawless and uneventful countdown, liftoff occurred on-time at 10:39 a.m. EST. The 16-day research mission will include FREESTAR (Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research) and the SHI Research Double Module (SHI/RDM), known as SPACEHAB. Experiments on the module range from material sciences to life sciences. Landing is scheduled at about 8:53 a.m. EST on Saturday, Feb. 1. This mission is the first Shuttle mission of 2003. Mission STS-107 is the 28th flight of the orbiter Columbia and the 113th flight overall in NASA’s Space Shuttle program.

Approximately 33 seconds after T-0 and liftoff of Space Shuttle Columbia, several particles are observed falling away from the -Z portion of the LH solid rocket booster ETA ring. Particles were identified later as probably pieces of the instafoam closeout on the ETA ring.

At approximately 80-84 seconds after T-0 and liftoff of Space Shuttle Columbia, a large piece of debris is observed striking the underside of the LH wing of the orbiter. The debris appeas to originate from the area of the -Y bipod attach point on the external tank. No damage to the orbiter Thermal Protection Systems was apparent.

STS-107 Crew

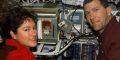

Astronauts Laurel B. Clark and Rick D. Husband, STS-107 mission specialist and mission commander, respectively, are pictured near supportive equipment for experiments on the SPACEHAB Research Double Module aboard the space shuttle Columbia.

Astronaut William C. McCool, STS-107 pilot, is pictured on the aft flight deck of the Earth-orbiting space shuttle Columbia.

A few of the STS-107 crewmembers pose for a photo in the SPACEHAB Research Double Module aboard the space shuttle Columbia. Clockwise from the bottom are astronauts David M. Brown, mission specialist; Michael P. Anderson, payload commander; Kalpana Chawla, mission specialist; and payload specialist Ilan Ramon. The Combustion Module-2 facility is visible in the background. Ramon represented the Israeli Space Agency.

Columbia and the STS-107 crew were lost over east Texas during the landing descent to Kennedy Space Center on Feb. 1, 2003, approximately 16 minutes before landing.

Space shuttle Columbia disintegrates as it hurtles across North Texas, February 1, 2003, on its way to Florida.

Recovering the Space Shuttle Columbia

This is an overview of the floor of the RLV Hangar. To date, 35,319 pieces of Columbia debris have been shipped to KSC; 1,218 have been identified and placed on a grid in a configuration of the orbiter. The Columbia Reconstruction Project Team is attempting to reconstruct the bottom of the orbiter as part of the investigation into the accident that caused the destruction of Columbia and loss of its crew as it returned to Earth on mission STS-107.

Fifteen years ago, on February 1, 2003, a sonic boom jarred Special Agent Brent Chambers as he was preparing to mow his lawn outside of Dallas on a chilly Saturday morning.

“I knew it was something bad,” said Chambers, now retired. He jumped in his car, turned on the police radio, and learned the news: NASA’s space shuttle Columbia had broken up as it re-entered the atmosphere. The deep rumble, which started just before 8 a.m. Central time, marked the explosive end of the shuttle and the tragic death of all seven astronauts on board.

As the noise faded, debris started raining down into eastern Texas and western Louisiana.

No one knew immediately why Columbia fell. But the nation couldn’t help but think about the 9/11 terror attacks less than 18 months earlier. “It was a time when people were concerned about terrorism, and it couldn’t be ruled out right away,” said Michael Hillman, another FBI Dallas special agent.

Before NASA could provide any answers, it needed to recover as much of the shuttle as possible. More importantly, the crew needed to be found. The Federal Emergency Management Agency coordinated the overall disaster response, and tasked the FBI with finding, identifying, and recovering the crew.

Agents and professional staff also helped secure classified equipment and safely contain and recover hazardous materials. Chambers led an Evidence Response Team, while Hillman led a Hazardous Evidence Response Team.

About 500 FBI employees from Texas and Louisiana eventually worked the recovery effort. They were part of a massive team of professionals and volunteers—more than 25,000 people from 270 organizations helped search 2.3 million acres.

Special Agent Gary Reinecke, a supervisor at the FBI’s Evidence Response Team Unit out of Quantico, Virginia, helped coordinate the Bureau’s recovery efforts. He and several agents with expertise in handling hazardous materials flew down in a Bureau jet, then deployed to a staging area near Lufkin, Texas.

“I had no idea what to expect when I got down there,” said Reinecke, now retired. “It was just swarming with astronauts.”

Searchers spread out across the countryside and sent coordinates to FBI teams if they came across suspected remains.

“After we determined we had found a crew member, we documented the scene like we would a crime scene—we mapped it and took pictures. But in this case, we didn’t keep any evidence. We turned everything over to NASA,” Reinecke said.

A NASA astronaut accompanied each FBI team that responded to reports of victim remains.

“We ended up forging a very close relationship with these astronauts,” Hillman said. “They quickly learned that we had the utmost respect and dedication to getting their friends and colleagues back.”

The remains of all seven astronauts were recovered, despite the obstacles of terrain and the scope of the search. Searchers combed through pine forests, hundreds of thousands of acres of underbrush, and boggy areas. Parts of the shuttle were found in Lake Nacogdoches and the Toledo Bend Reservoir.

Fortunately, the FBI has developed an expertise in responding to disasters of all types. “This is where we work best—during a national emergency. We were all highly trained. Our whole team was very well prepared and very well organized,” Chambers said.

“We’ve always been good at processing massive scenes,” agreed retired Special Agent Amy Ford, who led an Evidence Response Team from the FBI’s New Orleans Field Office. Many of the team members involved in the search had rotated through one of the crash sites from the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

The rural location of the search also presented challenges in initially identifying human remains. “This is where people hunt. Searchers were finding bones right and left. Most turned out to be animal bones, but we had to check and verify everything,” Ford said.

In addition to recovering the crew—all within a five-mile area—searchers also recovered about 38 percent of the shuttle, according to NASA: more than 84,000 pieces of the orbiter, weighing about 84,900 pounds.

“Sometimes you would find a piece that was two inches by two inches. A tile. Then sometimes you’d find a piece the size of a Volkswagen Beetle,” Hillman said. To this day, FBI offices still receive calls about potential shuttle debris being found.

FBI employees each spent several weeks or more assisting with the search, often working 12-hour shifts. FBI New York’s Underwater Search and Evidence Response Team helped locate and recover debris under water. The Firearms-Toolmarks Unit at the FBI Laboratory later helped find serial numbers on damaged tiles, which helped NASA determine the cause of the crash—a thermal breach in the left wing that led to structural failure.

“The FBI was a critical part of the Columbia recovery effort,” explained Ronald B. Lee, a NASA engineer and emergency manager at the Johnson Space Center. Lee said the FBI helped rule out sabotage and terrorism early on as possible causes of the disaster, helped locate crew members, and helped catalog recovered debris. “NASA thanks the FBI for its work bringing our crew home, as well as all the men and women who helped NASA during this very difficult time,” Lee added.

The FBI helped recover the remains of all seven crew members of the space shuttle Columbia. (From left) David M. Brown, mission specialist; Rick D. Husband, commander; Laurel Blair Salton Clark, mission specialist; Kalpana Chawla, mission specialist; Michael P. Anderson, payload commander; William C. McCool, pilot; and Ilan Ramon, payload specialist representing the Israeli Space Agency. Photo courtesy of NASA

Residents of Hemphill, Texas erected a memorial to mark where the remains of one of the space shuttle Columbia crew members were found. The FBI helped locate the remains of all seven crew members after the February 1, 2003 tragedy. Photo courtesy of NASA

PHOTO CREDIT: NASA or National Aeronautics and Space Administration