Astronomers have found a new cosmic source for the same kind of water that appeared on Earth billions of years ago and created the oceans. The findings may help explain how Earth’s surface ended up covered in water.

Astronomers have found a new cosmic source for the same kind of water that appeared on Earth billions of years ago and created the oceans. The findings may help explain how Earth’s surface ended up covered in water.

New measurements from the Herschel Space Observatory show that comet Hartley 2, which comes from the distant Kuiper Belt, contains water with the same chemical signature as Earth’s oceans. This remote region of the solar system, some 30 to 50 times as far away as the distance between Earth and the sun, is home to icy, rocky bodies including Pluto, other dwarf planets and innumerable comets.

“Our results with Herschel suggest that comets could have played a major role in bringing vast amounts of water to an early Earth,” said Dariusz Lis, senior research associate in physics at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and co-author of a new paper in the journal Nature, published online Oct. 5. “This finding substantially expands the reservoir of Earth ocean-like water in the solar system to now include icy bodies originating in the Kuiper Belt.”

Scientists theorize Earth started out hot and dry, so that water critical for life must have beendelivered millions of years later by asteroid and comet impacts. Until now, none of the comets previously studied contained water like Earth’s. However, Herschel’s observations of Hartley 2, the first in-depth look at water in a comet from the Kuiper Belt, paint a different picture.

Herschel peered into the comet’s coma, or thin, gaseous atmosphere. The coma develops as frozen materials inside a comet vaporize while on approach to the sun. This glowing envelope surrounds the comet’s “icy dirtball”-like core and streams behind the object in a characteristic tail.

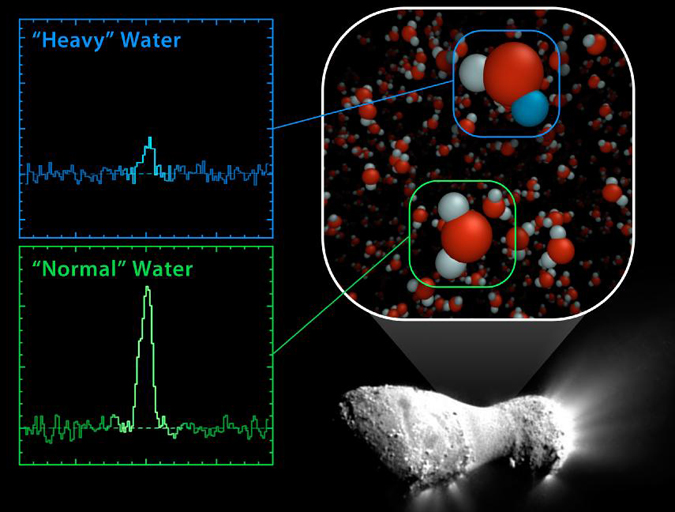

Herschel detected the signature of vaporized water in this coma and, to the surprise of the scientists, Hartley 2 possessed half as much “heavy water” as other comets analyzed to date. In heavy water, one of the two normal hydrogen atoms has been replaced by the heavy hydrogen isotope known as deuterium. The ratio between heavy water and light, or regular, water in Hartley 2 is the same as the water on Earth’s surface. The amount of heavy water in a comet is related to the environment where the comet formed.

By tracking the path of Hartley 2 as it swoops into Earth’s neighborhood in the inner solar system every six and a half years, astronomers know that it comes from the Kuiper Belt. The five comets besides Hartley 2 whose heavy-water-to-regular-water ratios have been obtained all come from an even more distant region in the solar system called the Oort Cloud. This swarm of bodies, 10,000 times farther afield than the Kuiper Belt, is the wellspring for most documented comets.

Given the higher ratios of heavy water seen in Oort Cloud comets compared to Earth’s oceans, astronomers had concluded that the contribution by comets to Earth’s total water volume stood at approximately 10 percent. Asteroids, which are found mostly in a band between Mars and Jupiter but occasionally stray into Earth’s vicinity, looked like the major depositors. The new results, however, point to Kuiper Belt comets having performed a previously underappreciated service in bearing water to Earth.

How these objects ever came to possess the tell-tale oceanic water is puzzling. Astronomers had expected Kuiper Belt comets to have even more heavy water than Oort Cloud comets because the latter are thought to have formed closer to the sun than those in the Kuiper Belt. Therefore, Oort Cloud bodies should have had less frozen heavy water locked in them prior to their ejection to the fringes as the solar system evolved.

“Our study indicates that our understanding of the distribution of the lightest elements and their isotopes, as well as the dynamics of the early solar system, is incomplete,” said co-author Geoffrey Blake, professor of planetary science and chemistry at Caltech. “In the early solar system, comets and asteroids must have been moving all over the place, and it appears that some of them crash-landed on our planet and made our oceans.”

Herschel is a European Space Agency cornerstone mission, with science instruments provided by consortia of European institutes. NASA’s Herschel Project Office is based at the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which contributed mission-enabling technology for two of Herschel’s three science instruments. The NASA Herschel Science Center, part of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at Caltech in Pasadena, supports the U.S. astronomical community.

The Same Here as There

New measurements from the Herschel Space Observatory have discovered water with the same chemical signature as our oceans in a comet called Hartley 2 (pictured at right). Previously, astronomers thought icy comets impacting on a young Earth had deposited only about 10 percent of the water comprising our oceans. The new findings, however, suggest that comets played a much bigger role. The image of comet Harley 2 at top right was taken by NASA’s EPOXI mission. The image at bottom right is an artist’s concept of a comet.

Heavy and Light Just Right

Using the Herschel Space Observatory, astronomers have discovered that comet Hartley 2 possesses a ratio of “heavy water” to light, or normal, water that matches what’s found in Earth’s oceans. In heavy water, one of the two hydrogen atoms has been replaced by the heavy hydrogen isotope known as deuterium. Hartley 2 contains half as much heavy water as other comets analyzed to date

Herschel’s “Heterodyne Instrument for the Far Infrared,” or HIFI, was used to obtain the spectral signatures of the water molecules, as shown here in the graphs. The image of comet Harley 2 was taken by NASA’s EPOXI mission.

Links

For NASA’s Herschel website, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/herschel

For ESA’s Herschel website, visit: http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/Herschel/index.html

WASHINGTON -- Oct. 5, 2011 - Dwayne Brown - Headquarters, Washington. Whitney Clavin - Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. RELEASE: 11-338 SPACE OBSERVATORY PROVIDES CLUES TO CREATION OF EARTH'S OCEANS. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech